As far as this website is concerned, the page could turn out to be the start—or the final word—on our illustrious ancestor, François Vallé.

I can't help but be proud that I am a descendant of François Vallé, a very wealthy and historically very important person in Upper Louisiana in the 18th century. I can't help but be ashamed that I am a descendant of François Vallé, a very wealthy slave-owner in Upper Louisiana in the 18th century.

The proud half of my brain feels chastened by the fact that I descend from Vallé's illegitimate offspring, Marguerite, whose mother was probably a slave, as well as the fact that, by the time I was born, there was no wealth to inherit. The ashamed half of my brain feels absolved by the fact that I descend from Vallé's illegitimate offspring, Marguerite, whose mother was probably a slave, as well as the fact that, by the time I was born, there was no wealth to inherit.

Ekberg, Carl J.

Everything I know about my famous ancestor comes to me via Carl J. Ekberg, the great chronicler of Upper Illinois. A proper historian like Ekberg himself would have to square this author's assessment against historical documents or other biographical sketches, if any were to be found. But I am not a proper historian; in fact I'm just a software engineer. And I'm pretty content with the wealth of information Ekberg has laid out in his many books.

François Vallé and His World

During my research into Our (Supposed) Indian Ancestry I learned of the existence of a biography of Marguerite Vallé's father—François Vallé and His World: Upper Louisiana Before Lewis and Clark by Carl J. Ekberg.

If you only like military history, this is not the book for you. But if you like the kind of history that gives you a sense of life in the distant past, I think you'll enjoy it. It is extremely thorough and carefully documented, and the life of this illiterate pioneer who moved from a small town in Quebec to become one of the richest men of Upper Louisiana makes for a very interesting read.

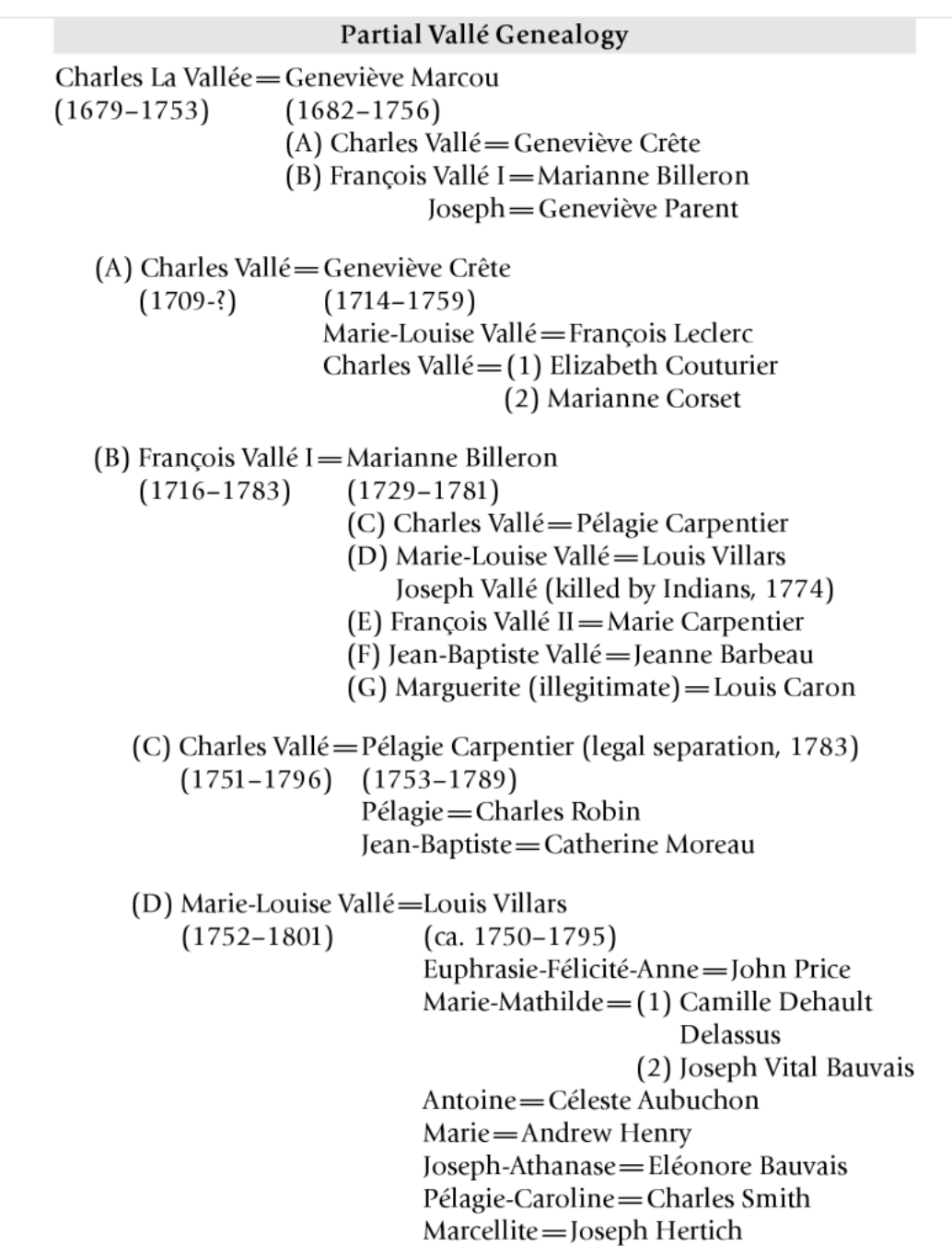

Genealogy

Let's start with some of the genealogical information Ekberg provides. Here's the book's partial family tree, shamelessly stolen from pages 122-123. François and his immediate descendants are in the "B" node; Marguerite and hers appear in the "G" node. As you study the "G" node, you might think that our AuBuchon link to Marguerite runs through Pélagie, whose first husband was an AuBuchon. But you would be mistaken. If you scrutinize the ancestor chart at AuBuchon Family Tree you'll see that our AuBuchon link runs through Marguerite's daughter Caroline, whose own daughter, Melanie Celeste Pepin, married Antony Moses/Moyin/Maise/Moise AuBuchon. (I suppose that eventually I'm going to have to figure out what his real middle name was.)

As for the genealogical record going in the other direction—from François's father Charles La Vallée back in time and east in geography—Ekberg doesn't offer much. He gives us what information is known in the first few pages of the book:

- François was born on January 2nd, 1716 in Beauport, Quebec.

- His father, Charles La Vallée, was born in Beauport around 1679 to Pierre La Vallée and Marie-Thérèse Le Blanc.

- Charles's father and uncle, the brothers Pierre and Jean La Vallée, left St. Saëns, near Rouen, France in 1657 or so, heading for Quebec in what was at the time called New France. A 1763 estimate has about three thousand people living in New France at the time, about a third having been born there. (This explains why so many of these early colonists seem to have their own Wikipedia pages.) For a separate source on Pierre and Jean, see Our Ancestors Pierre and Jean Vallée.

Marguerite Vallé

Marguerite Vallé was my great-great-great-great-great grandmother and the illegitimate daughter of François Vallé. Unfortunately, at the time Ekberg wrote this book (circa 2002), nothing was known about the girl's mother. He could only speculate that the woman was probably an African or Native American slave. It is fairly easy to find genealogical websites claiming to provide additional information about her (I mention some of these contentions in Our (Supposed) Indian Ancestry), but there seems no good reason to interpret these claims to be anything other than specious.

Here I document most of what Ekberg has to say about Marguerite.

The bulk of what he has to say starts near the end of Chapter 4.

Marguerite, François Vallé I's illegitimate daughter, presents us with the largest mystery of his life. She was born in about 1760, twelve years after François and Marianne had married and six after the entire Vallé family had moved to Ste. Genevieve. Marguerite was clearly the product of an adulterous relationship, and no bones were made about it. The words fille naturelle fairly leap off the page of both her civil marriage contract and her parish marriage record, because no other documents pertaining to the Vallé family contain that discreetly euphemistic phrase. We have no clue as to who Marguerite's mother was, or whether Marguerite was a "love child" (a product of a serious affective relationship between her parents) or simply a "lust child"; more likely the latter. Given the rarity of illegitimacy within the white Creole population of the region, Marguerite's mother was likely an Indian or black slave woman, but this is merely speculation.

White traders in Upper Louisiana often had Indian concubines, who, while remaining with their tribes, bore children by white men. Both Auguste and Pierre Chouteau kept second "wives" in Indian villages, partly to foster trading relationships and partly for sexual gratification. The children produced by these miscegenational and adulterous couplings were the basis for early Missouri's large métis population, which has become a book-length subject unto itself. But the white trader-Indian concubine model does not fit François Vallé well at all. First, by the time Marguerite was born, François had settled into his rather sedentary existence as planter and captain of the militia in Ste. Genevieve. He was no longer plunging into the Ozark foothills in pursuit of lead or furs, nor even traveling on business to New Orleans. Second, Father Pierre Gibault stated flatly in Marguerite's marriage record that she was a native of Ste. Genevieve. However, no baptismal record for her has been positively identified, and it is possible that Gibault, not having arrived in the Illinois Country until 1768, incorrectly assumed the place of Marguerite's birth. Third, traders did not normally integrate their métis children into their white families; Auguste and Pierre Chouteau certainly did not. As Tanis Thorne has pointed out, in Upper Louisiana "mixed-blood children were very rarely reared in family settings." Marguerite, however, was most assuredly raised in the Vallé family, although not as a full equal with her half siblings. When all is carefully considered concerning the identity of Marguerite's mother, a clear answer remains beyond our ken. It is one of those many matters of fact that everyone in old Ste. Genevieve knew, and likely gossiped about, but that is quite inaccessible to us. Perhaps some day documents will be discovered that will shed additional light on this fascinating case, and descendants of Marguerite and her husband, Louis Caron, will have the satisfaction of knowing just who their mysterious and interesting ancestor was. (p. 153-154)

There are other mentions of Marguerite scattered throughout the book. Here are my notes on some of them:

-

Being illegitimate, she couldn't take part in the family inheritance after her parents died. But François saw to it that her marriage contract contained a "handsome" dowry which included a black slave and some land. (p. 155)

-

"Marguerite herself could not sign her marriage documents, for she was illiterate; meanwhile, all her legitimate half-siblings had been taught to read and write. In this we likely again see the deft hand of [François Vallé's wife] Marianne Billeron, who was more literate than her husband and who provided her own children with a modicum of schooling." (p. 155)

-

The social structure in 18th century Upper Louisiana was extremely patriarchal, a situation which was enshrined in law. This obliged Marianne Billeron to "bear the pain of having her husband's illegitimate daughter raised in her household." (p. 156)

-

Regarding Marguerite's marriage to Louis Caron: "François Vallé was evidently not fully confident about the character of Louis, the man who was about to become his son-in-law, and he arranged to insert a clause in his daughter's marriage contract that provided some guarantees, at least for François's lifetime: Marguerite and Louis were forbidden to sell the slaves and the land provided in her dowry until after François Vallé had died." (p. 193)

-

"Illegitimacy within the white community was rare, and François Vallé's illegitimate daughter, Marguerite, likely had an Indian or (possibly) a black mother, whose identity remains unknown." (p. 121)

- This is one aspect of Upper Louisiana society which I would like Ekberg, or anyone with good researching chops, to delve more deeply into. Here Ekberg writes that white illegitimacy was rare, while in the long quotation from p. 153-154 above, he makes it sound fairly commonplace. Or perhaps in this instance he is speaking of Kaskaskia in the latter half of the 1700s, while in the other he is referring to all of Upper Louisiana for the century as a whole. In either case, what I'd like is for someone to go through the church records of all children born outside of marriage and try to determine what happened to them. But I suppose that there simply isn't enough information to be found.

In the next quotation, Ekberg helpfully speculates on how it might have come about that a fille naturelle would be living in what would otherwise have been a typical Creole household in the Illinois Country. (While you read this, keep in mind that Marguerite was born in 1762.)

At the beginning of their marriage, François and Marianne either had trouble conceiving children, or she was prone to miscarry her pregnancies. Their first child was born almost four years after their marriage, a time lag that was rare in colonial Illinois. As already noted, this situation provoked enough concern to induce François and Marianne to amend their marriage contract out of fear that they might never produce direct heirs. Once their luck changed, however, Marianne produced children in a steady succession. Between 1751 and 1753, Charles, Marie-Louise, and Joseph were born. There was then roughly a four-year hiatus until François fils was born in January 1758, with Jean-Baptiste following in September 1760. Marianne Billeron's fertile period lasted only one decade, and she was but thirty-one years old when her last child was born. She had obviously not yet arrived at menopause, and there is simply no way to know what ended the Vallé regime of producing children. One may speculate that when her husband began a sexual relationship with the woman who bore his illegitimate daughter, Marguerite, sexual intimacy between François and Marianne ceased; or, alternatively, that when for some reason Marianne could no longer physically sustain sexual intercourse, François began a relationship with another woman. In either case, Marianne and François continued to be close partners in all other aspects of their lives, for it must be understood that eighteenth-century marriages were not the romantic affairs about which we fantasize today. (p. 121-124)

.png)

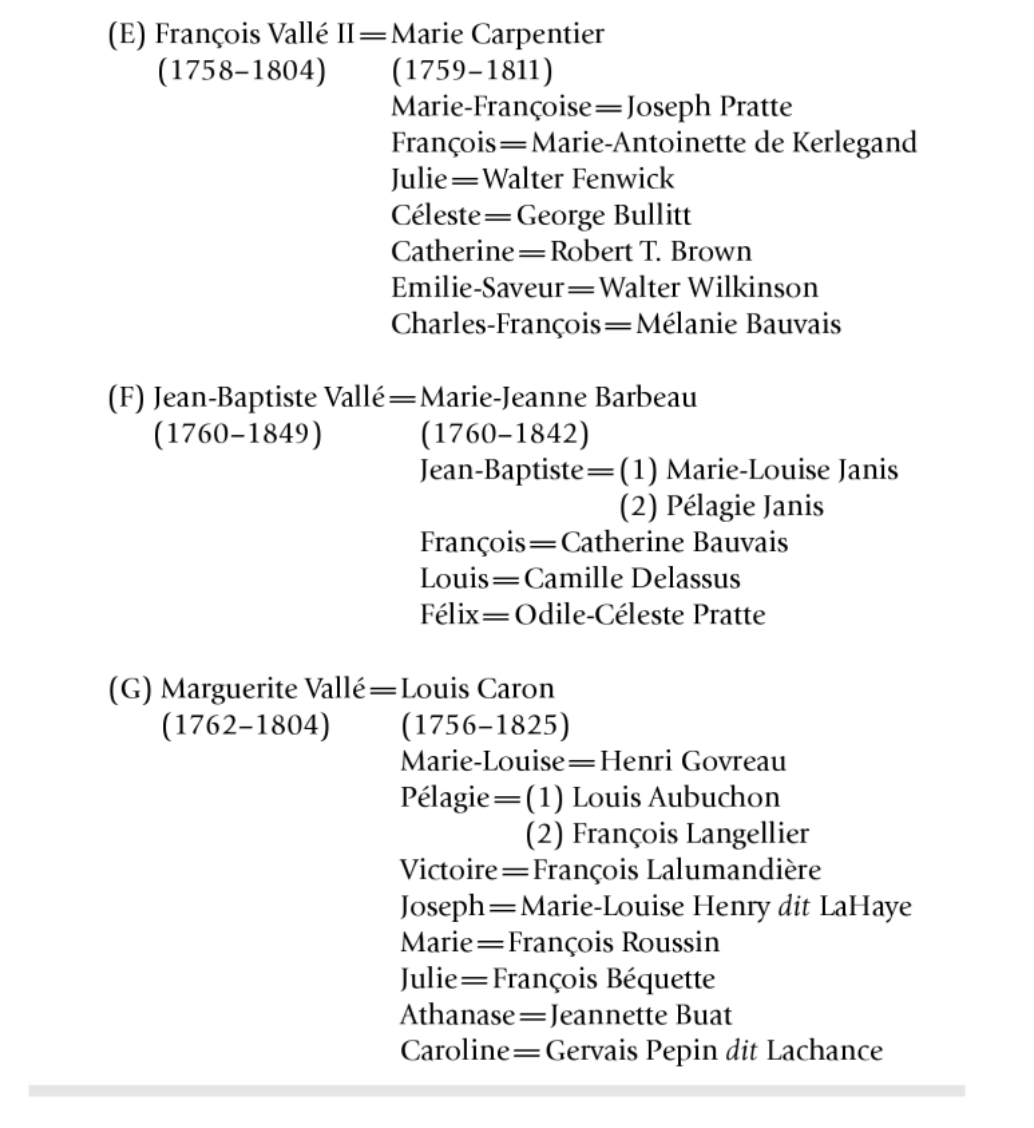

On the right is an image of what is, technically, a record of the record of Marguerite's marriage to Louis Caron. Which is to say that, a hundred or more years after the fact, the parish or the diocese asked somebody to go through the old church records, originally written in French, and put the bare essentials into a new register written in English.

Hers is the second on the page. Louis Carron's parents are both listed. Marguerite is not given a surname, and her parentage reads only, "Illegitimate daughter of François Vallé." The last column, listing the witnesses to the marriage, has, "Relatives & friends." (The image was found at FamilySearch.org.)

On the topic of Marguerite I'll provide one more item, though it comes from another of Ekberg's books, which we'll cover later on this page.

- “Marguerite, for whatever reasons, was a favorite Christian name for Indian women, both free and slave.” (Stealing Indian Women, p. 66)

- My take on this is that it almost seems to settle the matter that, if Marguerite's mother was a slave, she was Native American rather than African.

"Vallé, Marianne Billeron", in the Dictionary of Missouri Bibliography

Being the authority on the Family Vallé, it makes sense that Ekberg was asked to pen the entry on François's wife, Marianne, for the Dictionary of Missouri Bibliography (1999). Here is what he says about Marguerite.

In addition to these six children there was a seventh child, Marguerite, whom Vallé raised in her household. Marguerite was the illegitimate daughter of François Vallé, but the evidence suggests that Marianne accepted her into the family as one of her own. Marguerite was perhaps the product of a passing liaison between François and an Indian woman, but in any case Marianne's acceptance shows a wonderful generosity of spirit. (https://books.google.com/books?id=6gyxWHRLAWgC&pg=PA764#v=onepage&q&f=false)

Notice that here Ekberg is hagiographic as compared to his more cynical take on Marianne's role in the family dynamic in the François Vallé and His World—for example, see the quotation above from p. 155.

Stealing Indian Women

Ekberg's Stealing Indian Women: Native Slavery in the Illinois Country, published in 2010, has nothing on Marguerite, but a fair amount on François Vallé, and a great deal on slavery in Upper Louisiana. (For still more on slavery in New France see Tiya Miles' The Dawn of Detroit.)

The quotation below doesn't actually come from this book, but from the François Vallé biography. However, it very neatly summarizes the historical incident that would become the germ for Ekberg's later work.

Between the spring of 1773 and that of 1774 occurred the most curious, complex, and lengthy case with which François Vallé ever dealt as civil judge in Ste. Genevieve. The case unfolded on both sides of the Mississippi, British and Spanish; it involved a farrago of exotic frontier characters—whites, blacks, reds, and at least one métis; it brought together free persons and slaves, soldiers and civilians, men and women; it included drunkenness, fornication, eavesdropping, maroonage, grand larceny, alleged murder, and the only autopsy on record from colonial Upper Louisiana. The case was never fully resolved, perhaps because Vallé never really had his heart in it. It all began on a balmy spring Sunday morning in 1773, when a group of friends, including a métis hunter named Céladon, filched a pirogue in Ste. Genevieve and crossed the Mississippi to carouse in Kaskaskia. Kaskaskia, where the British colonial regime had little presence, was a better place for carousals than Ste. Genevieve, where François Valle and the Spanish commandant helped maintain a more decorous environment. Twists, turns, and convolutions took the case through the stealing of an Indian slave woman, her subsequent death from a gunshot, the abduction of another Indian slave woman, and her disappearance with Céladon into the wilderness along La Rivière de l'Eau Noire (Missouri's present-day Black River, which in the eighteenth century was better known for deer hunting and beaver trapping than for recreational canoeing). (François Vallé and His World, p 114)

With these lines in the Vallé biography, Ekberg summarizes this particular legal matter in a way that only whets the appetite. You can see that his curiosity has been piqued, that he would like both to learn more and tell us more. So it comes as no surprise that he soon completed Stealing Indian Women, in which this perplexing story is explored as deeply as the historical record allows.

It's a good read, this book. But, as with the provenance of Marguerite, much of the detail of the incident is now lost to history. Since, being a historian, Ekberg is reluctant to delve much in speculation, even after finishing the book you are left feeling that the matter hasn't been fleshed out. Personally, I think that the story needs the kind of liberty that only a historical novelist is allowed. You might say it begs for a good Hollywood treatment. In a novel or a film this event would somehow be related to Marguerite's entry into the world; but they occurred 13 years apart, so it is hard to imagine any true historical connection.