This page and the next tell the story of Jean Baptiste Janis, who fought for the Americans against the British in the Battle of Vincennes.

The AuBuchon Family Tree runs from my grandmother and grandfather back through many generations, some lines extending all the way to France in the 1600's. The tree provides an occasional place name or date, but there is almost no detail about any of these people. One exception, however, concerns Jean Baptiste Janis, who, it says, "fought with the Americans at the Battle of Vincennes."

I found this line too tantalizing to resist. My research began on the Internet, eventually extending to inter-library loan requests in New Jersey for out-of-print books about Illinois and Arkansas. Although the research continues—there are a few gaps I would like to fill in—on these pages you'll find what I've learned so far, which includes:

- Some detail on the Janis line of the family—and indeed, on all the French-speaking Creoles in the Illinois Country—just before and just after the American Revolution.

- A brief history of the Battle of Vincennes, which unfortunately does not provide any information about Jean Baptiste specifically.

- The U.S. Senate version of a bill that would have given Jean Baptiste $10 per month in return for his service at Vincennes.

- The full text of a speech in the U.S. House of Representatives in support of the House version of the same bill, which does its best to turn Jean Baptiste's feats into the stuff of American legend.

- The result of the U.S. Congress's decision whether or not to turn the bill into law.

There's a lot more here than I originally intended to write, so feel free to use the page contents at the side to skip to whatever you find most interesting.

In His Own Words (Nearly)

It's not a war journal or a letter to a friend, but, after much digging, I have found what comes close to a description of Jean Baptiste's revolutionary war experience in his own words.

Some Background

First let me briefly put it in historical context. Jean Baptiste Janis was born in 1759 in Kaskaskia, a small town on the Mississippi River in present-day Illinois. At the time, this was part of New France, a vast if vaguely-defined region covering much of what today is the eastern part of Canada, the American midwest and the area around New Orleans. His parents had migrated there from Quebec or Montreal, and Jean Baptiste grew up amongst people who identified themselves as Creoles—French citizens born in the New World.

The year of Jean Baptiste's birth marked the mid-point in the Seven Years War between France and England, the North American theater of which is called the French and Indian War, pitting the French with their Indian allies against the English colonists. The war ended in 1763, and France lost, big-time. They ceded to England all of their territory east of the Mississippi, and to Spain all of their territory to the west. (Wikipedia has an excellent map showing the consequences of the war.)

This left Jean Baptiste and his French compatriots under British rule. Many Creoles crossed the river for Ste. Geneviève, which had been founded in 1740. Those who remained in the Illinois Country liked neither the British nor the English colonists on the east coast, but, after the American Revolution began, if forced to take one side over the other, they generally chose that of the Americans. Their Indian allies, on the other hand, tended to side with the British.

In 1778, in the middle of the war, Jean Baptiste turned 19 and was still living in Kaskaskia. One morning the residents woke up to find the town had been taken over by the Americans in the middle of the night. Their leader was the charismatic George Rogers Clark, in the Virginia militia. For reasons unknown—but probably not simply because they were inspired by the principles laid out in the Declaration of Independence—about a hundred Frenchmen, including young Jean Baptiste Janis, decided to enlist in Clark's company. He had a daring plan to surprise the British at Vincennes, 180 miles to the east. In February of 1779, his mix of French settlers and Virginia backwoodsmen set off. The getting-there was very difficult, but Clark's men took Vincennes without losing a single soldier.

Four years later, the Americans won the war and began pouring into Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. The victors brought with them scorn for the land practices—and, more generally the way of life—of the French settlers who had come before them. In response, and like many other Creoles, Jean Baptiste took his family across the river to Ste. Geneviève, still under Spanish control. In 1800, thanks to a treaty between France and Spain on the other side of the Atlantic, they briefly enjoyed a return to French rule for a time, until the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 once again put the French Creoles under American dominion. And once again they found themselves overrun by Americans, but this time with no place to flee. Missouri became a state in 1821.

What was a period of wealth and expansion for the Americans was, of course, a time of devastation for the Native Americans. While the French Creoles did not perish, their culture did, and while some Creoles thrived, many lost their land in the transfer of Missouri from Spanish to American control.

Jean Baptiste was one of these. In 1833 he was 74 years old and impoverished. At that time, the American government was becoming increasingly conscious of the debt it owed to the soldiers who had fought, unpaid, in its war for independence. More and more veterans and their widows were beginning to receive compensation. Jean Baptiste set about taking the steps necessary to obtain the same for himself, which included the paperwork verifying and attesting to his contribution to the American cause. So that year he made a formal petition to the United States Congress.

The Petition

To the Senate & House of Representatives of the United States in Congress Assembled

Oppressed with age and infirmity, and in want of the many comforts of life, the undersigned begs leave respectfully to present this petition to the Congress of the United States.

Your petitioner states that in the summer of 1778, Kaskaskia was taken by Colonel George Rogers Clark of the Virginia line. he was then young and ardent and although a stranger to the laws, customs, language and institutions of the Americans, he became animated in support of the great cause for which they were struggling, and on many occasions manifested his devotion in a way as he believes to secure the entire confidence of the army and of its officers.

Your petitioner further states, that in the course of the summer a company of volunteers was organized composed of the French inhabitants on a call from Col. Clarke. In this company your petitioner was appointed an Ensign by his Excellency Patrick Henry then Governor of the State of Virginia which commission is exhibited with this petition.

Your Petitioner states that this Company was required to be ready for active service on a minute's notice, that many of its members were employed as hunters and spies and required when necessary to perform garrison duty.

Your Petitioner further states that the term of time for which Col. Clarke's men were enlisted having expired, many of them returned to their homes, which had the effect of weakening his force to an alarming extent and rendered his situation in that vast wilderness critical in the extreme. About this period Col. Hamilton, commandant at Vincennes, commenced assembling an army of British & Indians with the avowed purpose of not only expelling his enemies from Kaskaskia and Cahokia but to drive the Americans East of the mountains. At this juncture Col. Clarke determined on his daring expedition against Vincennes. Your petitioner further states that without the aid of the French inhabitants of Kaskaskia and Cahokia the power of the Americans was unequal to the task of capturing Vincennes, at that time the center of British influence. But in this emergency Col. Clarke called upon the French to take part in the expedition as volunteers, which call was promptly responded to. Two Companies were accordingly raised, and equipped at their own expense, one under the command of Captain Charleville of Kaskaskia, the other under Captain McCarty of Cahokia. Your petitioner acted as ensign in the company of Charleville. These two companies added to the Americans made a combined force of 170 men. With this small array Col. Clarke marched in the month of February 1779, and after swimming rivers and creeks, wading for miles through waters amid snow & ice, suffering the extremes of hunger and fatigue, they surmounted every obstacle and towards the close of the month, arrived before Vincennes, where the flag of the United States was planted by the hand of your petitioner within gun shot of its walls.

Your petitioner further states that after a few days' siege, conducted with consummate skill by Col. Clarke, this important place fell and with it forever the British power in the valley of the Mississippi. Your petitioner further states that, during the whole period the American troops held possession of Kaskaskia & Cahokia, they were quartered on the inhabitants or sustained by requisitions. Your petitioner's friends and relations made advances for which compensation to this day has never been made. For these services and sacrifices, your petitioner prays that his name, during his few remaining days, be placed on the Pension Roll, or such other provision made for him as the justice of his case would seem to demand. Your petitioner begs leave further to say that in the year of 1796 he being then a married man and the father of 8 children removed from Kaskaskia to St. Genevieve in the Spanish province of Louisiana with the intention of acquiring lands for his family under the liberal policy pursued by the Spanish Government in making donations to settlers. He made application for a conception of 8000 arpents which was granted by the Sp. Governor. On the transfer of Louisiana to the Americans a law was passed by Congress requiring that all concessions should be registered by a certain day. Your petitioner, unacquainted with the English language, never heard of this law and his claim not being recorded in accordance with its provisions was consequently lost to him. Thus your petitioner served this country in his youth without compensation and in his old age finds himself deprived by law of that property which was generously bestowed on him by another Government.

(signed)

John Baptiste Janis (Sen.)?

of Missouri

A couple of notes:

- Jean Baptiste served as an ensign, whose duty, in addition to engaging in combat, was to carry the military unit's flag. This should clarify the line in the petition which goes, "arrived before Vincennes, where the flag of the United States was planted by the hand of your petitioner within gun shot of its walls."

- As I discuss in Five Signatures, there's good reason to believe that Jean Baptiste did not sign the document himself.

Sources. For this transcription I started with that of Will Graves at at Pension application of Jean Baptiste Janis. I then made some light edits to his version. To see the images of the actual documents—written in longhand—go to Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application File S. 15,901, for Jean Baptiste Janis, Virginia.

What came of Jean Baptiste's petition to Congress? Even 25 years ago historians believed that Jean Baptiste Janis' request for compensation was denied (see for example Lankford). However, as explained below, I have independently verified that Congress approved his request. Thanks to the fact that institutions like the Library of Congress and other sites mentioned below are making historical records available on the Internet, it seems I have the chance to rewrite history.

That's the end of my abridged history of Jean Baptiste Janis, veteran of the Revolutionary War. What follows are the details, where practically everything described above receives considerable elaboration, starting with how to pronounce our hero's last name.

A Little French

The Janis line of our family goes back to France. Now, usually I have no objection to anglicizing a French word or name, but the difference between the English and French versions of this name is so great that I think in this case it's worth a little time and energy. The name is not pronounced like the Janis in Janis Joplin. Rather, it sounds like this. (If you have trouble with the page linked to, see the Using the "How to Pronounce" Website page.) In case the link is bad or you don't have sound on your computer, let me give you the sounds.

- The 'j' is pronounced like the 's' in the word Asia.

- The 'a' is pronounced something like the 'a' in Ma.

- The 'n' should be no problem.

- The 'i' is pronounced like the double-'e' in feet.

- The final 's' is silent. (At least, it would be today. But records kept in French at that place and time sometimes spelled the surname as "Jannice", suggesting that sometimes the "s" was silent, and sometimes not. See Note 2 of Marriage of Nicolas and Marie Louise.)

A Little Geography

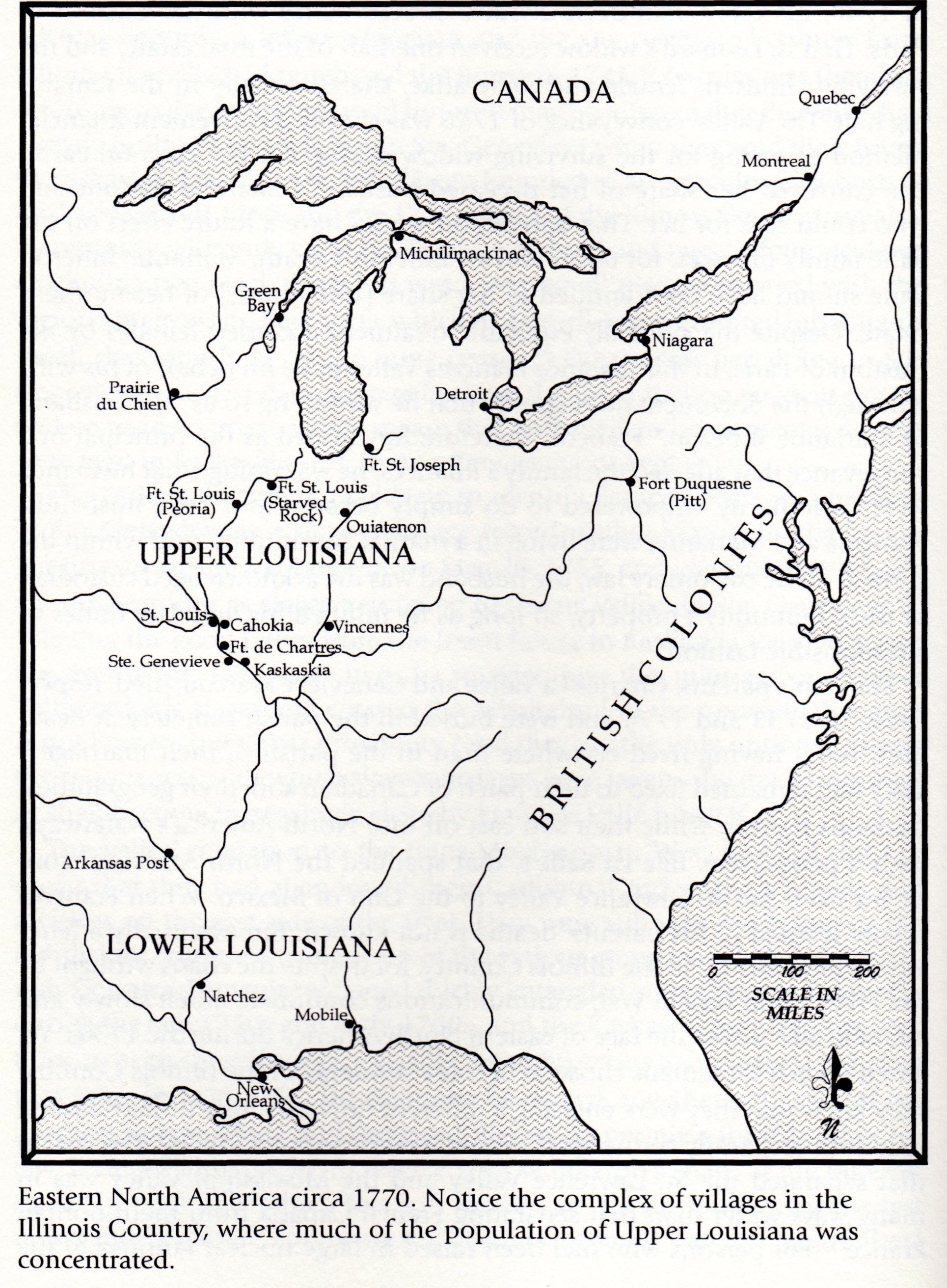

This map, from Carl J. Ekberg, François Vallé and His World (a biography of a patriarch of another branch of the family tree), shows all the important towns in this discussion: Ste. Geneviève and Kaskaskia, on opposite sides of the Mississippi, as well as Vincennes, 180 miles to the east. Fort Duquesne, later Fort Pitt, and Pittsburgh after that, plays a small role as the starting point for George Rogers Clark on his journey down the Ohio to Kaskaskia. Way up in the northeast sit Montreal and Quebec, the stepping stones my ancestors used on their way to Upper Louisiana, aka the Illinois Country.

Somewhere on the Web I ran across a map detailing the villages in that part of the Illinois Country which Jean Baptiste and his family habituated. I'm sorry but I've lost the source. The map is hand-drawn and therefore fairly hard to read. In other words, it is more evocative than informative. But it's still fun to have a look at. Cahokia is at the top; Kaskaskia at the bottom.

The Name "Jean Baptiste"

Jean Baptiste is the French version of John the Baptist. In her book, Kaskaskia Under the French Regime, Natalia Meree Belting, while discussing some of the festivals the French Creole celebrated, mentions just how common this given name was.

The fête day of St. Jean Baptiste, patron saint of Canada and most popular patron in Illinois, marked midsummer, and was celebrated with ancient pagan customs. On the evening of June 24, the elders of the village hunted for sacred herbs to provide future remedies, and the children went from door to door begging for fagots to burn. At nightfall the wood was heaped in a great pile, and the oldest habitant or perhaps the curé, threw on a flaming brand. In the church there were special services the next day and another procession. Those men and boys who had been named for the saint, and there was one Jean Baptiste in practically every Kaskaskia family, kept their birthday anniversaries then as was the custom in Catholic countries. (p. 70)

While digging into old church records for The Janis Line, Pt. 1, I soon learned that the name Jean Baptiste was so common it is frequently abbreviated as "Jean Bte." Our particular Jean Baptiste sometimes signed his name as "Bt Janis," or "Bte. Janis," dropping the first name entirely. We'll see that later in these pages.

The Janis Family

It's six generations back from my mother, Corinne AuBuchon Kurlandski, to Jean Baptiste Janis, the hero of this 18th Century tale set in the heart of North America. But our family tree for the Janis line goes back even further, to the Champagne region of France in the mid-1600s. All this and more is explored on the The Janis Line, Pt. 1 page.

Here's the part of our tree for Jean Baptiste Janis going back to his grandparents, François Janis (born in France) and Simone Brousseau (born in New France, possibly Quebec City) who married in Trois Rivières, Quebec in 1704.

├── Jean Janis == Marie Paquet ├── François Janis (b. 1676) == Simone Brousseau (1684-1746) ├── Nicolas Janis (1720-1804) == Marie Louise Thaumur (1737-1791) ├── Jean Baptiste Janis (1759-1836)

So according to the family tree, our hero, Jean Baptiste Janis, (starting from the bottom) had a father whose name was Nicolas Janis, and a grandfather named François Janis, and a great-grandfather named Jean Janis. But my most valuable source on the Battle of Vincennes casts some doubt on this information with regard to his grandparents, and therefore with regard to his great-grandparents as well. (That's why I call this site Adventures in Genealogy. It's never easy going for long. Usually it seems as difficult as Jean Baptiste's trek through the Indiana wilderness to Vincennes. Which we will get to eventually, I promise.) These questions are explored in the The Matter of Two Nicolases section of the "Janis Line" pages.

The valuable source referred to above is "Almost 'Illinark': The French Presence in Northeast Arkansas," by George E. Lankford. For the most part, we will follow him on our journey to Vincennes. Here he is discussing Nicolas Janis, born in 1720, the father of Jean Baptiste Janis:

Nicholas Janis was an important man both in French Illinois and in his family, as his consistent signature suggests; it is always just “Janis,” without further specification. [... He] appeared as a young man in Kaskaskia and Sainte Geneviève around the middle of the century. His first appearances in the records were in 1751, when he sold a house and land in Kaskaskia for four hundred livres, suggesting he had already been there long enough to purchase or build that property. That same year he married Marie Louise Taumur, daughter of Jean Baptiste Taumur dit La Source and Marie François Rivard, who had long been members of the Kaskaskia community. Ekberg thinks that he first settled in the fledgling village of Sainte Geneviève for a few years, before selling his property there and moving to the older Kaskaskia. What is clear is that he quickly became one of the pillars of French Illinois, established at the principal village on the east side of the Mississippi River.

Let's follow Lankford's reference above to Ekberg's Colonial Ste. Genevieve: An Adventure on the Mississippi Frontier. Ekberg writes:

Also of interest for the early history of the Old Town are two men, Janis and Chaponga, who were cited in Rivard's grant as adjoining property owners and must therefore have owned land in Ste. Genevieve's Big Field before Rivard requested his grant. It seems certain that this Janis was Nicolas Janis, who married a sister of the Lasource brothers, Marie-Louise, in April 1751, and who probably moved to Ste. Genevieve with his new bride. Logically, Janis and his wife should have appeared in the town's census for 1752, but they did not. (p. 35-36)

Perhaps he did not appear in the census because by that time he and Marie-Louise had moved across the river to Kaskaskia? In any case, Nicholas and Marie Louise had six or seven children. Lankford continues:

They apparently grew prosperous at their endeavors, for when the French and Indian War came to an end in 1763, they became part of the British empire rather than fleeing to another area of the world remaining under French domination. They were well aware of the fact that Arkansas Post, Ste. Geneviève, and the young St. Louis had become Spanish, but they seemed content to be British in Kaskaskia. C. W. Alvord described them this way: “Among the gentry, which was a rather elastic term, were also many well-to-do men, who had risen to prominence in the Illinois or else possessed some patrimony, before migrating to the West, which they increased by trade.... These members of the gentry lived far more elegantly than the American backwoodsman and were their superiors in culture. Their houses were commodious and their life was made easy for themselves and families by a large retinue of slaves.” A hint of the quality of life in Kaskaskia comes as a historical detail: when Nicholas Janis’s daughter Félicité married Vital Bauvais in 1776, one of the gowns in her wedding trousseau was made from material which had come from France that same year.

Life in British Illinois was not without its problems, though, and when George Rogers Clark arrived to conquer the Illinois on behalf of the new United States in 1778, he found that no battle was necessary, for the Kaskaskia French received them with enthusiasm and embraced the end of English control. They fed Clark’s army and even provided volunteers for the winter march to capture Vincennes, a brief campaign whose victory made a hero of young Jean Baptiste Janis. (p. 97)

"Young" is right: having been born in 1759, Jean Baptiste was just 19 or so when he joined Clark's troops to head for battle. The French and Indian War had ended when he was just four, so it is possible that he had never fired a gun at another person before—especially if his life had been as easy as Lankford describes.

The Battle of Vincennes

Lead-Up

Present-day Illinois and Indiana—the "Illinois Country," named after the Illinois Indians—were originally settled by the French. After the French and Indian War, the British gained control of this area and the Spanish soon won the lands west of the Mississippi. There were only about 2,000-5,000 French settlers living in the Illinois Country, largely concentrated in Kaskaskia, Prairie du Rocher, Cahokia and Vincennes. The French did not tend to live in isolated farms scattered far from one another.

Then the American Revolution began. While the famous battles—the stuff we learn about in school—were taking place along the East Coast, there was also considerable engagement in the interior of the continent.

The American Indians were for the most part aligned with the British, who discouraged the colonists from encroaching on Indian land. The French settlers in the Illinois Country would have wanted to remain neutral, no doubt preferring to be left alone. But when the Americans and British engaged in Upper Louisiana, the French would often be forced to choose a side, as we shall soon see.

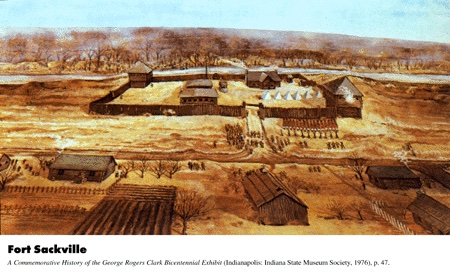

In late 1778 a force of about 90 British regulars and 200 Native Americans arrived at the town of Vincennes, located on the Wabash River between what would become the states of Illinois and Indiana. The British commander, Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton, immediately set to work improving the fortifications of the stockade next to the town, at the time called Fort Sackville. The French townspeople were forced to swear an oath of allegiance, and from the men among them Hamilton formed a militia of about 250. Some of these men would serve the British well. However, Hamilton would have been keenly aware of the French militia's weak loyalty to the British crown.

(Drawing from Facebook post of the Indiana Historical Bureau.)

Over in American-occupied Kaskaskia, George Rogers Clark recognized that, come spring, Hamilton's forces would regroup and begin operations against Kaskaskia and any other American-held towns in the Illinois Country. Outnumbered, his men would have little hope against them. Clark therefore conceived of a plan to take Fort Sackville and Vincennes in a surprise winter attack.

Clark had no more than 200 men, and was losing many of them because their enlistments were expiring. He managed to persuade about half to extend their enlistment eight months, and began recruiting French settlers into his small army, which would include our hero, Jean Baptiste Janis. In the end Jean Baptiste was just one of about 80 other Creoles to join the ranks of Clark's regiment. (See Wikipedia, "Illinois campaign", which, citing Lowell H. Harrison's George Rogers Clark and the War in the West has: "[Clark] set out for Vincennes on February 6 with 170 men, nearly half of them French militia from Kaskaskia.").

The Creole Volunteers

Why did these four score Kaskaskia French volunteer? Certainly, there was a long antipathy between the French and the English, the result of centuries of rivalry and open conflict between the two nations. In addition, nearly a full year before Clark's campaign began, France officially entered the war, after signing the Treaty of Alliance in the early part of 1778, and the Creoles would naturally have been inclined to take the side of their mother country.

There were also religious considerations. Clark enjoyed the support of Père Gibault, the village's pastor (curé). Understandably, Gibault was primarily concerned with religious liberty: under which government, English or American, would his Catholic flock be able to practice their faith unhindered? Clark, technically fighting under the banner of Virginia—there not yet being a United States of America for him to represent—was able to assure him that under Virginia law the Catholic Church would be protected (Wikipedia, "Illinois campaign").

However true and valid these motivations may have been, I don't feel they sufficiently explain the enthusiasm the French Creoles displayed for the American cause.

What do I mean by the Creole "enthusiasm"? First and foremost, the number of Creole volunteers whom Clark was able to persuade—about 80, as we've said. What percentage of the male population was this?

Let's do a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation. I can't find numbers for the population in 1779, but in 1764 the Creole population was 1,400, a drop from the population in 1752. (Brown & Dean in The French Colony in the Mid-Mississipi Valley, p. 47, citing "the census of D'Abbadie"). However, Ekberg says that the 1752 population was 1,380, which is less than 1,400, contrary to Brown and Dean's claim. We don't need to adjudicate that here—let's just say that both numbers are correct and take the average of the two. Ekberg goes on to mention that 43% of the population consisted of slaves, which means about 57% were Creoles. 1,390 X .57 = 792 Creoles in the Illinois country. Now, how much would the population have changed by 1779? On the one hand, populations tended to grow on the American frontier; on the other, we know that many of the Creoles, disgruntled under the British rule which began in 1763, moved across the river to the Spanish side. So let's say the population stayed more-or-less constant. 80 volunteers/792 Creole inhabitants = about 10% of the population. If there were as many women as men, that would come to 20% of the male population. However, there were more men than women in the Illinois Country, so let's just say that Clark managed to muster up about 15 percent of the men. That seems a significant number of volunteers from a population that were technical neutral vis-a-vis the war. (Militia Volunteers)

Moreover, it seems that the non-volunteering townspeople also displayed plenty of enthusiasm for Clark's call to arms against Vincennes. In writing his two histories, Clark emptied one inkwell after the other describing how he manipulated the psychology of everyone he encountered, from the the French villagers, to the Indian tribes, to the English holed up in Fort Sackville. I doubt that he was the Svengali he believed himself to be, but let's put that question to the side, at least temporarily, and consider how he describes the villagers of Kaskaskia in the week or two immediately prior to the start of the campaign in early February, 1779.

Orders were immediately issued for making the necessary preparations. The whole country took fire and every order, such as preparing provisions, encouraging volunteers, etc., was executed with cheerfulness by the inhabitants. Since we had an abundance of supplies, every man was equipped with whatever he could desire to withstand the coldest weather. (Conquest of the Illinois)

And here he is writing of Lt. Gov. Henry Hamilton, who commanded the British in Vincennes.

I conducted myself as though I was sure of taking Mr. Hamilton, instructed my officers to observe the same rule. In a day or two the country seemed to believe it. The ladies began, also, to be spirited and interest themselves in the expedition, which had a great effect on the young men. (Campaign in the Illinois)

Alberts has the following, but it is not cited and I cannot find any reference to this in his primary sources (which consist mostly of Clark's histories):

The [Creole] women busied themselves in sewing company, regimental, and Virginia flags. They made enough flags for an army of 1,000 men, but the patriot commander insisted that he would need them all in the campaign. (Alberts, p. 29)

(The flags belonged to Virginia because at that time the Illinois Country was claimed by Virginia, and Clark was, technically, working for that colony.)

Finally there is Clark's description of the day his small army left Kaskaskia for Vincennes:

On the fifth [of February] I marched, being joined by two volunteer companies of the principal young men of the Illinois, commanded by Captains McCarty and Francis Charleville. Those of the [regular, American] troops were Captains Bowman and William Worthington of the light horse. We were conducted out of the town by the inhabitants and Mr. Gibault, the priest, who, after a very suitable discourse to the purpose, gave us all absolution, and we set out on a forlorn hope indeed, for our whole party, with the boat's crew, consisted of only a little upwards of two hundred. (Campaign in the Illinois)

(Note his phrasing, "the principal young men of the Illinois". Does he mean "the very best"? That's not how principal is ordinarily used. More likely he means "the most important." Or, to be blunt, "of the most prominent families." To repeat Lankford, quoted above: Jean Baptiste's father, Nicolas, was "one of the pillars of French Illinois.")

To return to my point, I feel that Clark's campaign against Vincennes had generated too much zeal in the town than can be attributed solely to a long-held antipathy toward the English, the Mother Country's aligning herself with the Americans, or the abstract promise of religious liberty. Based on the evidence, there must have been more going on in the French Creole hearts than just that.

First of all, a hint of one thing which does explain this zeal can be found in the second paragraph of J.B.'s Petition (as quoted above):

Your petitioner states that in the summer of 1778, Kaskaskia was taken by Colonel George Rogers Clark of the Virginia line. he was then young and ardent and although a stranger to the laws, customs, language and institutions of the Americans, he became animated in support of the great cause for which they were struggling.

Now, I do not take these to be the actual words of Jean Baptiste—no more than I believe that it is truly his signature which adorns them at the end. But I do believe that whoever wrote them was expressing Jean Baptiste's memory of his feelings, a half-century later, as he related them in his native, humble French to the writer of the petition. What, then, did he and this anonymous writer mean by "the great cause" which the Americans were engaged in?

It could refer to some of the more high-minded ideals of the American Revolution ("all men are created equal," etc.), but more probably it's a reference to simple self-determination. Independence from England, in other words. A couple of times now, I've mentioned that many of the French Creole abandoned the Illinois Country in favor of the Spanish territory on the other side of the river once the English gained control.

So it's likely that, regarding the American Revolution, the French Creoles saw themselves in a similar, if until-then peaceful struggle against English rule. Since the end of French and Indian War they had had a taste of life under the British, and for the most part they didn't like it. (See Henry Pirtle note below.)

Secondly, George Rogers Clark was a magnetic and inspiring leader. Though they were strangers "to the laws, customs, language and institutions of the Americans," something caused Jean Baptiste and the other Creole volunteers to become "animated" in support of the American Revolution, and that something can only have been Clark and his fiery oratory. This American stranger had taken Kaskaskia from the English in the middle of the night, coming seemingly from nowhere and without a shot being fired. He had entertained the village with, apparently, one ball after another. And, mostly, he had talked, talked, talked. He had not received much formal schooling, so it is unlikely he spoke much French; and surely the young Creole men understood next to no English at all. So most likely, it seems to me, he communicated to the villagers through an interpreter. Which only makes his persuasive ability even more impressive.

Finally, we need to consider the situation these young men found themselves in. As Clark himself points out in the passage quoted above, most if not all of the French Creole volunteers were "young men." Jean Baptiste and his Creole camarades d'armes were born near the time of the French and Indian War. That means that their fathers were most likely engaged in the war itself, fighting on the French and Indian side against the English. On the frontier, war in its various forms must have been a rite of passage for young men. Now that France had abandoned their land, giving the Illinois Country to the English, who would be the mother country that these young men would fight for? Certainly not England. On top of this let us consider the fact that the young men were probably, like J.B., unmarried if not unattached, and of the age when it becomes a matter of urgency to end that state. "The ladies began, also, to be spirited and interest themselves in the expedition," Clark wrote, as I quoted above, "which had a great effect on the young men."

It seems to me, then, that these were much more powerful motivations for the enthusiasm the Creole evinced for the American Revolution:

- a deep empathy for the cause itself

- Clark's charisma

- the fact that most of the men who volunteered were at a time in their lives when they needed to establish themselves, both socially and, let's say, romantically

The Campaign & Battle

Clark devised a strategy of retaking Fort Sackville with two divisions—one by land and one by water. For the land attack, he would march east from Kaskaskia to Vincennes. The going would not be easy, he knew, as the winter had been very wet and much of the land between the two towns was flooded.

For the attack by water, he purchased a large Mississippi flat-bottomed boat and converted it into a row galley—an armed boat that primarily employed oars rather than sails for propulsion. After the retrofit, the boat, called the Willing, boasted two 4-pounder cannon and four swivel guns (lighter cannon mounted so that they could be turned in a wide arc). The boat was meant to carry 46 men and heavy equipment as well as ammunition. (Alberts, p. 29)

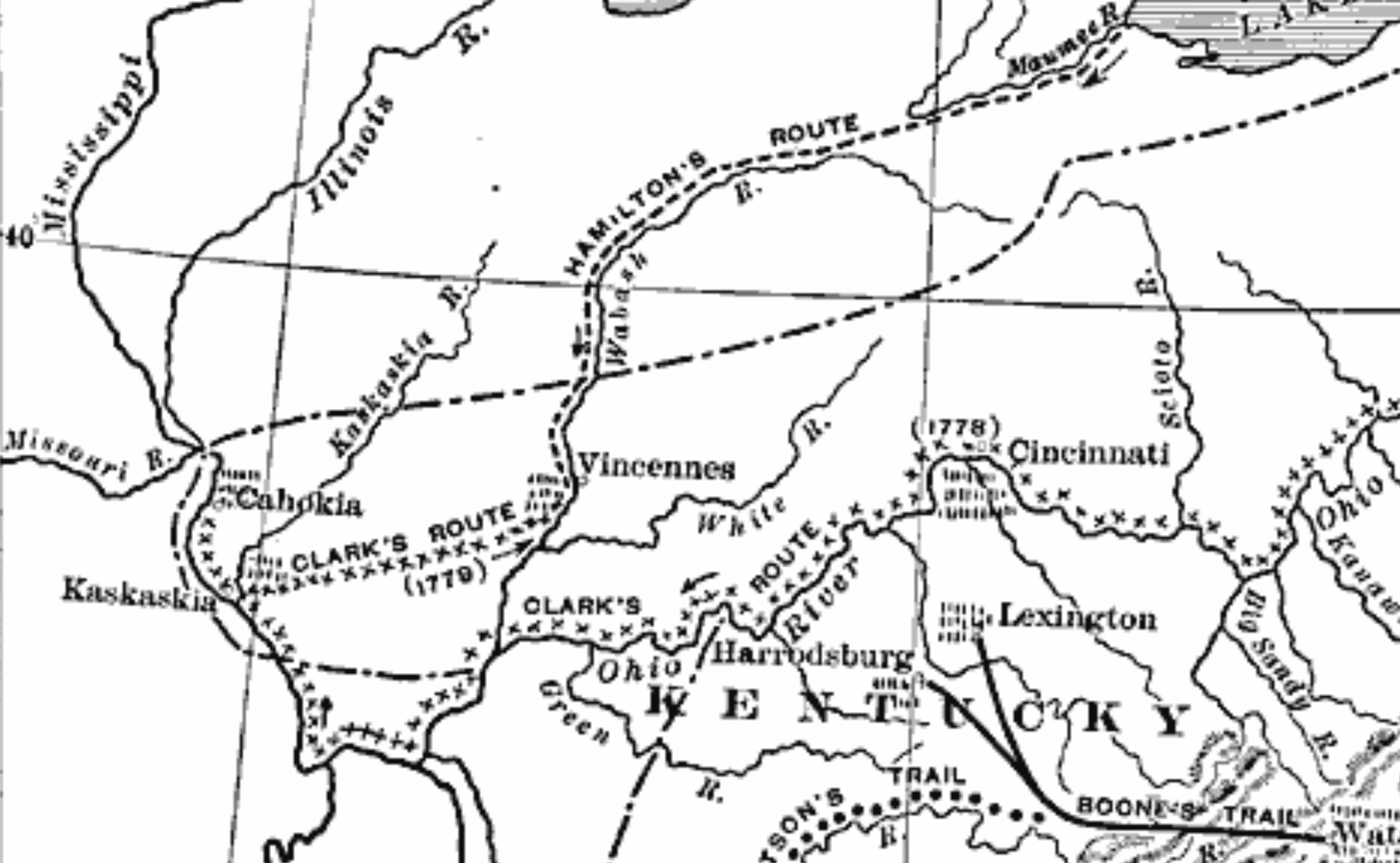

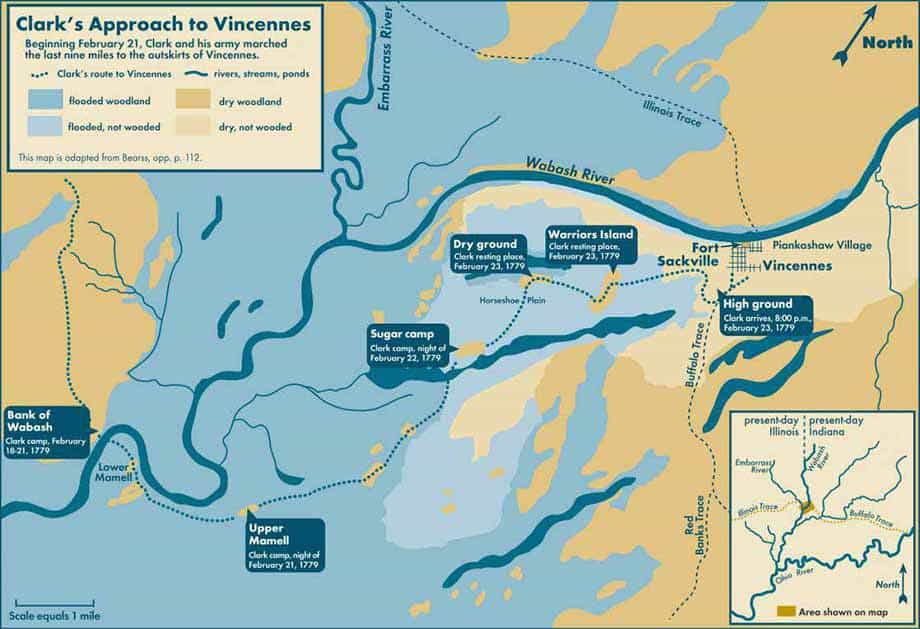

The map below is a close-up of one part of American Revolutionary War Operations in the West, 1775–1782. Hear's how to get your bearings:

- On the left, at the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, sits the village of Cahokia, across the water from what will later become St. Louis.

- To the south is Kaskaskia, and further south still is the point where the Ohio flows into the Mississippi. It's hard to find the label Ohio River on this map because of all the other labels. Look just above the "K" in the capitalized name KENTUCKY.

- Trace the Ohio upstream to Cincinnati. If you continued up the Ohio (right off the map in this case), you would reach Fort Pitt, present-day Pittsburgh.

- Almost midway between Cincinnati and Kaskaskia to its west lies Vincennes, on the Wabash River.

The map marks some of the military operations we have discussed. Along the Ohio River is the phrase "Clark's Route (1778)," with arrows and "x"s leading you downstream to the Mississippi, then upstream to Kaskaskia and Cahokia. North of Vincennes, the map marks Hamilton's route from Lake Erie on his way to capture Vincennes and Fort Sackville. Finally the map marks Clark's 1779 march overland from Kaskaskia, with the intention of taking both the town and the fort back from the British.

The Willing

The map does not mark the route the Willing and its crew took in order to attack Vincennes by water. The plan was for the boat to float down the Mississippi to the Ohio River, up the Ohio to the Wabash River, and up the Wabash until it was not far downriver of Vincennes. There the Willing would wait hidden until the land arm of the attack joined them.

While we're focusing on the map I might as well tell you that this plan went awry: the boat did not arrive in Vincennes until after the British surrendered the fort. Why? On the map, notice that the White River joins the Wabash south of Vincennes. The crew of the Willing had a number of navigation issues, mostly due to flooding, and the delay these issues caused was compounded when they accidentally turned up the White River instead of staying on the Wabash toward Vincennes. (I found reliable documentation on why the Willing was late to reach Vincennes hard to come by. The best sources I could find are Facebook pages—not the most trustworthy of sources, ordinarily, but in this case my concern was assuaged by the fact that both were posted by George Rogers Clark National Historical Park. They are:

- https://www.facebook.com/GeorgeRogersClarkNationalHistoricalPark/photos/a.194238817263770.42454.188817644472554/898773296810315/?type=1&_rdr; and

- https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=807466881424428&id=100064833692614&set=a.218724730298649.)

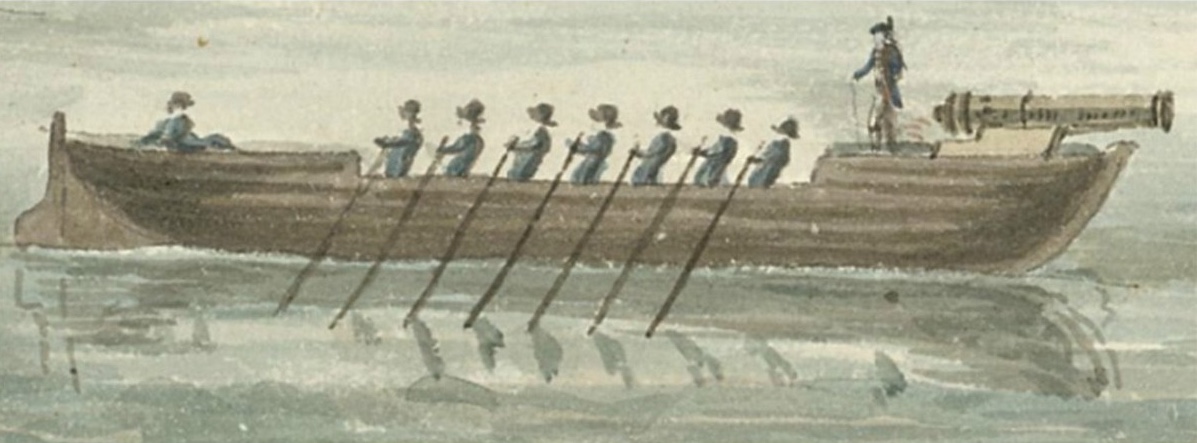

I wanted to find and share a picture of the Willing, or at least of what it might have looked like. The second of the sources listed above offers the image below.

The image is identified as a portion of James Hunter's 1777 work "A View of Ticonderoga from a Point on the North Shore of Lake Champlain." As for the size of the ship depicted, I count seven rowers and two people not rowing. Let's suppose that there are seven more rowers on the other side of the vessel: that would give us a total of 16 people in the boat. Since the Willing was meant to carry 46 as well as heavy equipment and supplies for Clark's land division of about 170, we can safely suppose that the actual Willing was roughly three times the size of this boat, maybe a little more.

Still in search of an illustration of what the ship might have looked like, I came across renderings of the Miami, which was the name of a row galley which Clark had built a few years later for defending the Ohio River.

This drawing is by Charles Waterhouse and entitled "Ohio River Row Galley, Summer 1782" (from A Pictorial History of the Marines in the Revolution). It's meant to show what the row galley the Miami might have looked like, which is described as requiring 110 men—approaching three times the number the Willing was meant to carry.

The Land Attack

On February 5th, 1779, Clark's march on Vincennes began. Their chief obstacle was not the cold but miles and miles of flooded plain. A good portion of the journey involved wading rather than hiking. The map below (currently at https://revolutionarywar.us/year-1779/battle-of-vincennes/ though it seems to have a habit of unpredictably wandering from one web page to another) shows the last nine miles of the march. It is color-coded to distinguish dry land (shades of brown) from flooded plains and woodlands (shades of blue). Enlarge the image by clicking on the link in the caption—a quick glance will immediately tell you just how much of the end of the trek lay under water. At places it was up to their shoulders.

On the Question of Horses

As we will see in Jean Baptiste's Affidavit, below, our hero swore under oath that he, quote:

accompanied Gen. Clark for Six months with the Continental Troops, and during this term of Service aided and assisted in taking Post Vincennes from the Royalists or Enemy of the United States, that he used a Horse during all the time while acting as Officer.

But horses play a very peripheral role in the various histories of this expedition, so much so that no illustration of the campaign that I have ever run across depicts a horse. In other words, based on my reading, this is not an issue that historians have spent much time considering. Perhaps I am breaking new ground here. So be it.

Let's document the horses that are mentioned in the several accounts I've come across.

1. Clark himself was mounted on a horse as he left Kaskaskia.

- "The next day at 3 p.m.—7 days after Vigo's arrival in Kaskaskia—Clark mounted a Spanish stallion and led his column out of the village." (Alberts, p. 29)

- "Clark rode a horse which had been brought from New Mexico—'The finest stallion by far that is in the country,' wrote the Colonel subsequently." (Butterfield, p. 308)

2. Some of the Americans in the expedition were in some way associated with the calvary.

- I have already quoted Clark on this point: "Those of the [regular, American] troops were Captains Bowman and William Worthington of the light horse." (Campaign in the Illinois)

- But does the fact that the men were "of the light horse", which refers to light cavalry, mean that they brought their horses along? If they had, wouldn't they have been mounted, like Clark himself? And if so, wouldn't that be mentioned in some history somewhere? Maybe not: There are very few original sources for this historical event; Clark nearly has a monopoly on them. And he is a rather self-obsessed autobiographer. So it is possible he neglected to mention anybody else who was also on horseback as they left Kaskaskia, Vincennes-bound.

3. They had pack-horses to carry supplies.

- From Captain Bowman's Journal:

- February 2nd: "A pack-horse master appointed and ordered to prepare pack saddles, etc., etc."

- February 5th: "Raised another company of volunteers, under the command of Captain Francis Charleville, which, added to our force, increased our number to one hundred and seventy men [torn off] artillery, pack-horses, men, etc.; about three o'clock we crossed the Kaskaskia with our baggage, and marched about a league from town."

-

From Clark's "Letter to Mason", explaining how they made their way across a flooded plain: "the rest of the way we waded, building scaffolds at each to lodge our baggage on until the horses crossed to take them." (https://www.in.gov/history/for-educators/all-resources-for-educators/resources/george-rogers-clark/letter-from-george-rogers-clark-to-his-friend-george-mason/letter-part-six/)

-

From Clark's The Conquest of the Illinois: "A feast was held every night, the company that was to give it being always supplied with horses for laying in a sufficient store of meat in the course of the day." (https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/Indiana/_Texts/Conquest_of_the_Illinois/6*.html)

The March to Vincennes

As a man or as a horse, and as a man with or without a horse, we can be sure that the march to Vincennes was a wet time for every participating two- and four-legged creature.

On February the fifteenth, ten days into their march, because they were now nearing the fort, orders were given that they could use firearms only in self-defense or to kill game. (Alberts; Bowman)

But game was not easily come by in the flooded landscape. By the 20th of February they had run out of food, and the most exhausted among them had to be shuttled from one dry patch to another by canoe. Wikipedia quotes the journal of Captain James Bowman where he characterizes the men as "very quiet but hungry; some almost in despair; many of the creole volunteers talking of returning." He added, "Those that were weak and famished from so much fatigue went in the canoes."

Alberts describes them as scrounging for hickory nuts and pecans on the ground, as well as roasting a fox for nourishment (p. 44). Nestor gives a little more detail, saying the men bagged the fox by frightening it from its den. They killed several opossums in the same way: "Each man got a bit or two of the gamy meat. Then they crowded around the fires and trembled away the endless night." (p. 124)

On the 23rd they were finally within striking distance of Fort Sackville. The harrowing 18-day march receded from their minds as they physically and mentally prepared for battle. Things began happening in quick succession now, rather than haphazardly spread over the course of weeks. (In the next few paragraphs we'll be following Butterfield.)

- The troops captured a French creole resident of Vincennes, who turned out to be a known ally. Through him Clark sent a letter to the people of Vincennes, saying that he intended to attack the fort that night, that those in the village who supported "liberty" should stay in their homes, while those who did not should go into the fort and defend it. The townspeople passed word from house to house but did not notify the British. (p. 324ff)

- At about sunset, the army approached Vincennes from a direction in which the village's houses obstructed the fort's view, thus ensuring that the British remained oblivious to their presence.

- Just before they entered Vincennes, Lieutenant Bayley and fifteen riflemen were detached to attack the fort. They were tasked with harassing the enemy until the village could be secured. (p. 328)

- At eight o'clock Clark entered the town, and he proceeded directly to the homes of a Major Legras and a certain Captain Bossoron (p. 330). (Different sources have different spellings of the latter surname.)

- Shortly thereafter, Bayley and his men reached an advantageous position and began firing on the fort. (p. 332, 334)

At some point in these proceedings, Legras and François Bossoron led Clark to some gunpowder they had hidden when the British had previously captured Fort Sackville and requisitioned all the powder in the town. What is not clear is whether this happened when Clark paid them a visit at 8:00, when he first entered the town, or now, after Bayley's attack had begun. Butterfield mentions it on p. 335, after the shooting had begun.

What Butterfield takes great pains to do is to dispel two myths which prevailed at the time he wrote his account, in 1904: (1) that Legras and Bosseron met Clark outside of the town, before the Clark had actually arrived there; and (2) that nearly all his small army's gunpowder had been ruined by march through the flooded plains (Note XCVIII on p. 716). Butterfield does say this, but regarding the second point, it is worth dispelling the story if untrue because it would be extremely irresponsible, if not a matter of gross negligence, for a military commander not to ensure his regiment's gunpowder was safely stowed for a long march through flooded territory during a time of inclement weather.

Butterfield does allow that Clark might have been low on gunpowder, especially since the nautical arm of the attack still hadn't arrived on the scene: "As might be supposed, ammunition was, at this juncture, scarce with the Americans, as most of the stores were on board the Willing."

In my own research, it appears that Myth Number 2 still has some life in it. For example, an article in Wikipedia has: "George Rogers Clark and his American forces arrived on 23 February 1779, his black powder ruined while wading across the Wabash River." (Wikipedia, "François Riday Busseron")

Alberts does not make the mistake of endorsing this falsehood. Instead he notes that Busseron was amongst the Vincennes residents serving in Hamilton's French militia, colorfully adding that after turning over the gunpowder to Clark, the Frenchman "hurried to the fort to report for duty, apologizing for having been unavoidably delayed" (p. 46).

We know that Busseron did not report the Americans' presence to the British inside the fort. What we don't know is whether he whispered a warning to his French compatriots also serving in the militia there. Alberts relates the story of a Mrs. Moses Henry who went into the fort to visit her husband. He was being held there under suspicion of passing information to the enemy. She is said to have whispered the news to her husband while passing him the dinner she had brought—tidings which he then relayed to the other Frenchmen there.

The Battle

The Americans opened fire on the fort at around sunset, taking Hamilton and his men by surprise. The British tried to respond with cannon, but the Americans shot at their gunmen through the open portholes. Moreover, since the Americans had taken cover behind the houses near the fort, the British commander feared that destroying the French dwellings would only turn the residents against him, as well as weaken the resolve of the French militia fighting from inside the fort on behalf of the British.

At some point during the night a Piankeshaw chief named Tobacco's Son (his name is also translated as Young Tobacco) arrived with about 100 warriors. Alberts refers to him as Clark's "old friend" (p. 47), but nowhere does he explain how, or for how long, the two knew each other. Tobacco's Son offered to assist in the siege of the fort, but Clark declined, because (according to Alberts) he feared that his men might not be able to distinguish them from the Indians fighting on the British side. Wikipedia categorically states that Clark declined the offer "likely due to his well-known hatred of Indigenous people."

The next morning Clark and Lieutenant Governor Hamilton began negotiating terms of surrender. During these negotiations, the Americans' chief advantage lay in Hamilton's false impression of the size of Clark's forces. At this point, circumstances gave Clark an opportunity to cause the Indians defending the fort to have second thoughts about their support of the British.

That is, perhaps, the most generous way of describing what Clark did. Wikipedia calls it "the most controversial incident in Clark's career." The American Battlefield Trust's page almost apologetically introduces the event as "one of the most controversial and brutal episodes of the frontier wars."

Since the shooting had stopped while negotiations were taking place, and since the British flag was still raised over the fort, a party of Indians and the British-organized French militia entered the town unaware of the American siege. Clark's men captured them. The French were released, but the four Indians were sat in full view of the fort and tomahawked to death. The Americans then scalped the prisoners and threw their bodies into the river. Aside from the fact that they never would have treated British prisoners this way, Clark's actions broke the military code of conduct because the incident occurred during a time of truce. (See George Rogers Clark note below.)

Historians seem to disagree whether this weakened or strengthened the resolve of the Indians inside the fort. In any case, Hamilton and Clark finally agreed on the terms of surrender, and the American flag was raised over Fort Sackville at 10 a.m. on the morning of the 25th.

The Wikipedia article, in the "Aftermath" section, lists 20 casualties--four American and 16 British. (I wonder if by "American" they are including the French Creoles, or if no French died.) There is no mention of the Native Americans whom Clark ordered his troops to tomahawk and scalp, or of any other Native Americans.

After the Revolution

Historians of war may disagree about the impact the Battle of Vincennes had on the American Revolution, but there is no dispute over who won the war. The British were forced to withdraw from the thirteen colonies as well as Upper Louisiana, while maintaining control of what would become Canada. The Americans would soon cross the Appalachians in increasing numbers, settling in the Illinois Country, which technically belonged to Virginia until the former colony ceded it to the United States. Eventually the separate territories of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin would be formed and join the United States.

These were not happy times for the Native Americans living there. Take for example the Piankeshaw, whose chief Tobacco's Son offered to assist George Rogers Clark in his attack on Fort Sackville: prior to the American revolution, this tribe was known to be less hostile to settlers than others. "The Piankeshaw are usually regarded as being 'friendly' towards European settlers. They intermarried with French traders and were treated as equals by residents of New France in the Illinois Country" ("Piankeshaw" in Wikipedia). In the late 1700's their population declined, hurt by warfare and economic circumstances. A hard winter followed by a drought in 1781 was devastating, and the increasing settlement by the Americans after the Revolution eventually drove them either out of the Illinois Country or into tribes resisting American encroachment. In 1818 they were finally forced to sign a treaty ceding much of their land to the United States. The few remaining tribes people eventually became part of the Peoria tribe of Oklahoma.

And what of the French Creoles living in Upper Louisiana?

After the Battle of Vincennes, in a celebratory speech delivered to the habitants of Kaskaskia, Clark declared: "In a short time you will know the American system which you will find, perhaps, in the beginning a little strange; but in the course of time you will find so much peace and tranquillity in it, that you will bless the day that you espoused the cause of the Americans." (Alvord's Kaskaskia Records, p. 80-83, dated 1779)

How the French Creoles would fare in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War was being considered outside of the Illinois Country as well. In a letter to Clark written in 1780, while the war was still ongoing, Thomas Jefferson wrote, "We approve very much of a mild conduct towards the inhabitants of the French Villages. It would be well to be introducing our Laws to their knowledge and to impress them strongly with the advantages of a free government—" but he continued the sentence with a much more salient, and immediate goal, "the training of their militia, and getting into subordination the proper officers should be particularly attended to." He ends the thought by returning to the high hopes of Creole assimilation which he began with: "We wish them to consider us as brothers, and to participate with us the benefits of our rights and laws." (Alvord's Kaskaskia Records, p. 144, dated 1780)

A noble goal, but it was never realized. Before the war had even ended, François Busseron—the French fur trader who had supplied Clark with the hidden gunpowder—was already having regrets about his support for the American cause.

By 1781, the Canadian residents of Vincennes had become frustrated with the Virginia government, depreciated US currency, and the Virginia militias that used or took their property without proper compensation. The leading citizens of Vincennes, including François Busseron, signed a letter of grievances to the governor of Virginia. Over the course of the American Revolution, Busseron extended up to $12,000 credit to Clark. None of this was ever repaid to him. He and all but one of his children died in poverty. ("François Riday Busseron" in Wikipedia)

The war ended in 1783. The Thirteen Original Colonies had won their independence. But the Articles of Confederation, which joined them, led to a federal government so weak it was scarcely a government at all.

American settlers began to move into Vincennes—70 families by 1786, most of them squatters occupying land near the fort. With them they brought an independent spirit, initiative, advanced technology, and some small amount of capital with which to begin to build and develop. But they also brought the problems inevitable to newcomers in a changing economy and in the clash of dissimilar cultures. They distrusted and detested the Indians, and with no one to regulate the Indian trade, they debauched them with their corn whiskey. They quarreled with the French habitants, whom they considered lazy, whose ancient customs they scorned, and whose local government they mocked. They corrupted the economy with worthless Continental currency and claimed ownership of more and more land, some of it devoted to communal use, much of it occupied by the French for generations. Fort Patrick Henry (old Fort Sackville) was stripped for building materials and left in ruins. Vincennes was in a state of virtual anarchy, almost in a reign of terror. (Alberts, p. 57)

It sounds as though the Americans were intent on making the land their own, at any cost, and they justified their ill-treatment of the French by despising their way of life. This is not unlike the way they treated the Native Americans.

Ekberg has a very interesting article which explains the communal nature of the Creole settlers' agricultural system, and he argues persuasively that it led to a mutually dependent, much less violent society than the system which American settlers would practice as they migrated into the Illinois Country. The communal nature of the Creole system required that farmers work together. It is easy to imagine how quickly the system would break down with the arrival of significant numbers of people who would refuse to participate.

Busseron died in 1791, two years after the U.S. Constitution was ratified. The new federal government was much stronger than what preceded it. However, this new stability did not significantly improve the lives of the Creoles living in the Illinois Country.

The Janis Family

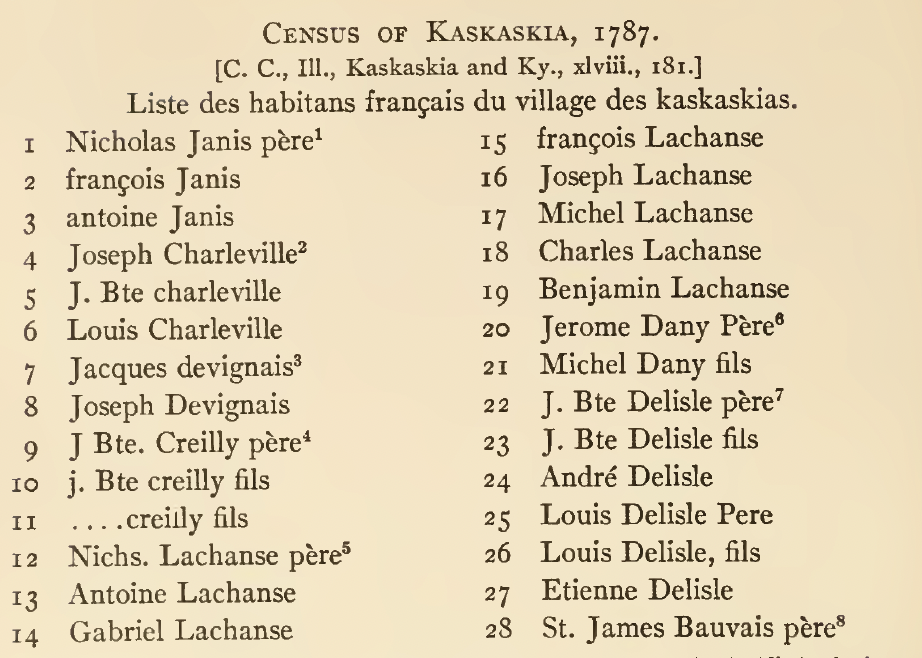

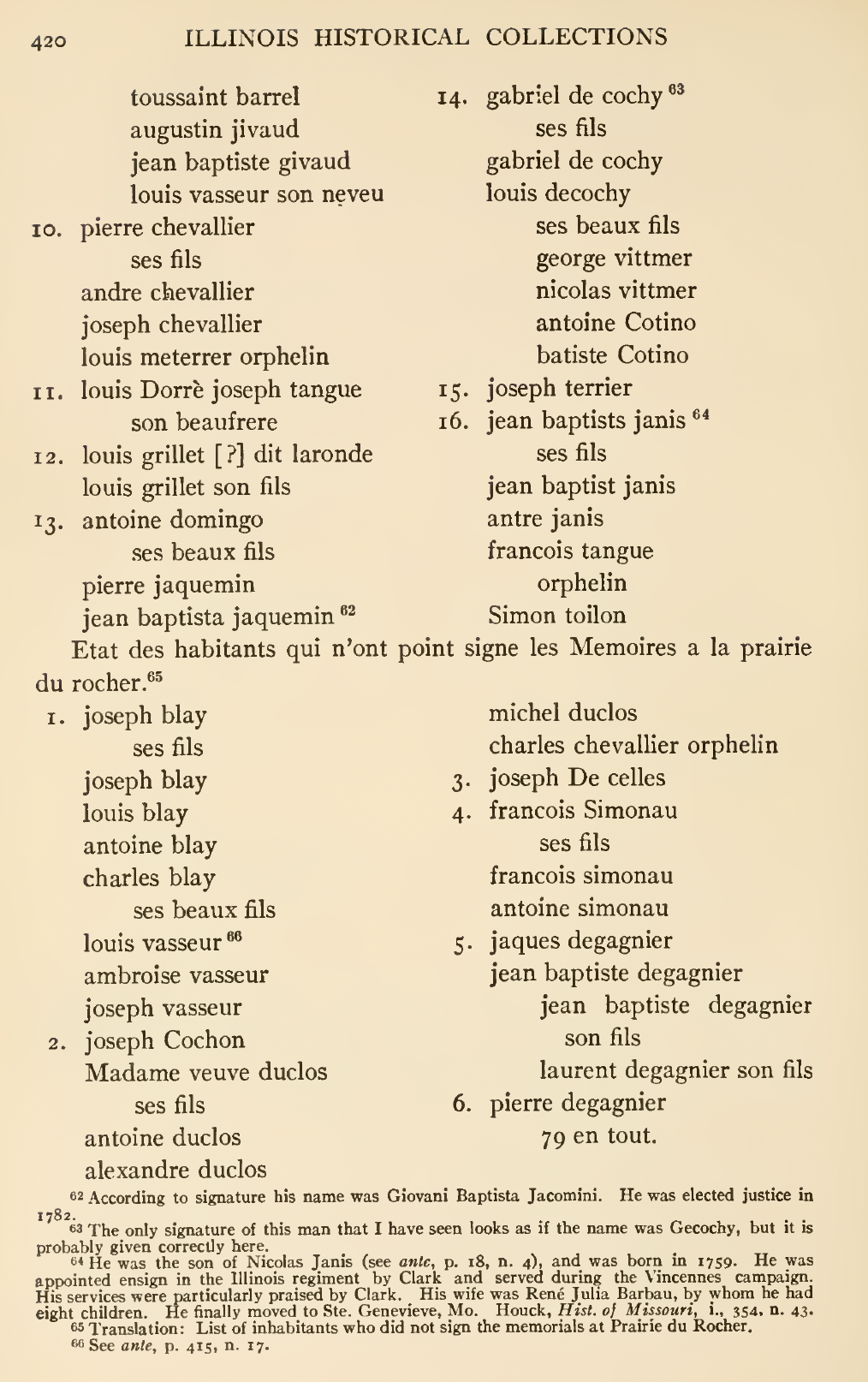

The 1787 Kaskaskia Census, given in Alvord's Kaskaskia Records (p. 414), records Nicolas Janis and two of his sons as Kaskaskia residents, but there is no mention of Jean Baptiste. Note that Nicolas and his two sons are the first three persons listed, which I think must say something about his prominence in the village at that time. To find Jean Bte., you have to look in the Prairie du Rocher census of the same year, where you'll find him with his two sons Jean Baptiste, Jr. and Antre (sic: André maybe?). His wife was from Prairie du Rocher; it seems reasonable to think that they decided to live there after they married so she could be close to her family. Perhaps Jean Baptiste was happy to acquiesce, if only to get out of his father's shadow. Alvord's reprint of the Prairie du Rocher census has this footnote concerning Jean Baptiste: He was the son of Nicolas Janis, and was born in 1759. He was appointed ensign in the Illinois regiment by Clark and served during the Vincennes campaign. His services were particularly praised by Clark. His wife was Rene Julia Barbau, by whom he had eight children. He finally moved to Ste. Genevieve, Mo. (p. 420) Note that, in the Prairie du Rocher census, the Janis surname is not #1 (as it is in Kaskaskia), but #16. This apparent fall from grace foreshadows what would eventually befall the name. (On the plus side, appearing in the #1 position in the Prairie du Rocher census is Barbau, the surname of Jean Baptiste's wife. The decline may have ended deep, but initially, at least, it seems to have been gradual.) Point of frustration: The writer of the footnote quoted above (one of the editors of the Kaskaskia Records, perhaps Alvord himself) does not cite the source for his claim that Clark had special praise for Jean Baptiste. In all my reading, I have not found another reference to this. From here we can return to Lankford's narration of the history of the Janis family. Like Busseron in Vincennes, Jean Baptiste's father, Nicolas, had served as a captain in the British militia in Kaskaskia. His duties there ended, of course, when George Rogers Clark took over the town. In 1779, the French citizenry made him a judge. Since the land was now claimed by Virginia, his authority as a justice—and, indeed, the power of the French to rule themselves— was considerably weakened. It was not clear who was in charge and a number of different English-speaking strangers arrived in the Illinois Country, each claiming to be the legitimate representative of the Virginia government. Thus began the final French exodus to the Spanish, the western, side of the Mississippi, a migration begun after France's loss in the French and Indian War against the British. All of the major Creole families seem to have disappeared from the official records there—the baptismal and marriage certificates, for example—except for the name of "Janis." While his neighbors crossed the river, Nicholas Janis held out in Kaskaskia through these years; the Janis family left in groups for Spanish territory in the late 1780s, but Nicholas did not leave until the end of the decade. Jean Baptiste and François and their families went from Prairie du Rocher to Sainte Geneviève. [...] It appears that Nicholas the patriarch did not move to Sainte Geneviève until 1790 or 1791. (p. 99) Ekberg, in Colonial Ste. Genevieve, says that Nicolas moved across the river in 1788, and at the time had 19 slaves, an indication that he was "well-to-do" (p. 428). The previous year, the Northwest Ordinance banned slavery in Illinois and the rest of the Northwest Territory—but only in principle, since in practice many slaveholders managed to keep their slaves for at least half a century longer. Even so, it is probably not coincidental that Nicolas moved across the river to what would become the slave-state of Missouri one year after the passage of the Ordinance, for in doing so he was able to eliminate all possibility of the statutory loss of his "investments." (See Slavery in Illinois in the footnotes.) What about Jean Baptiste? In his letter to Congress, quoted in the section above titled The Petition, Jean Baptiste wrote that he received 8,000 acres from the Spanish government after he moved to the Ste. Geneviève side of the Mississippi, and that he lost it all on the transfer of the Louisiana Territory to the Americans, leaving him, as he says at the very beginning, "oppressed with age and infirmity and in want of many comforts of life." He doesn't describe with any specificity what happened, but attributes it to his own weak English: "your petitioner unacquainted with the English language never heard of this law." Lankford doesn't fill in the details regarding Jean Baptiste in particular, but he provides some detail regarding the general case. As long as the settlers remained under the Spanish flag, possession and improvement of the land was sufficient title, but the transition to U.S. territorial status in the opening decades of the nineteenth century forced the regularization of land titles. The Board of Land Commissioners found themselves having to determine "legitimacy" for prior land ownership. Their task was complicated by land fraud—and the belated attempts by some of the Spanish commandants to give settlers legal grants before the Americans took over. The board's response was to set strict standards which had to be met in order to show the legitimacy of a claim, including proof that the claimants were actually living on the land prior to December 1803, or even earlier, and that they were farming significant acreage. Both the standards and the process of providing proof were difficult for the French, and they saw little chance of success. Moreover, there may have been some anti-Gallic bias involved, for the board refused to confirm the joint ownership of the commons in the French towns, and thus voted against the European settlement pattern itself. (p. 109) So the country for whose existence John Baptiste had gone to war would in the end take away his land and therefore his means of sustenance. How he and his grown children fed, clothed and sheltered themselves we do not know. But his father Nicolas Janis died in 1808, and Jean Baptiste watched his own son Jean Baptiste fils die before him in 1830 at the age of 56. It was just then, in the early 1830's, that the U.S. Government began the belated task of compensating its revolutionary soldiers for their unpaid service. A law was passed requiring proof of a minimum of six months of service in order to qualify for a pension. Though the details are murky from this vantage point, it seems that Jean Baptiste applied for the pension and with the application he sent his proof of service—but that the proof of service was lost in the mail or lost in government bureaucracy. And to serve as a temporary replacement for the lost proof of service, he worked with the local county government in order to provide an affidavit, signed under oath, that he had served the United States as a soldier, and not under only Colonel Clark. I provide the affidavit in full, then follow it with an executive summary for any readers who prefer to skim or hop over it entirely. State of Missouri County of Ste. Genevieve: SS Personally appeared before me a Justice of the Peace within and for the County aforesaid, Baptiste Janis who being duly cautioned and sworn, on his Oath deposeth and Saith -- That he is now Seventy-four years of age and a resident of the County of St. Genevieve aforesaid. That he was residing at Kaskaskia Illinois in what is now the County of Randolph and State of Illinois, when he received from Gen. Geo. Rogers Clark a Commission to act as an Officer in the Troops, and accompanied Gen. Clark for Six months with the Continental Troops, and during this term of Service aided and assisted in taking Post Vincennes from the Royalists or Enemy of the United States, that he used a Horse during all the time while acting as Officer, and that he has never received any Lands or money as pay for his Service from the United States or State of Virginia -- -- That he received and accepted a Commission from Governor Todd at Kaskaskia Illinois and served the United States or State of Virginia for Three months with the troops on Continental Service in Illinois Country, that he used a horse during all this time and has never received any Lands or money as pay for Service under this Commission or any other from the United States or State of Virginia. -- That he received a Commission as Ensign for the Troops stationed in the Illinois Country North West of river Ohio from Governor Arthur St. Clair and accepted and done duty as Officer for Three months under this Commission, and used a Horse during all this time, That he has never received any pay for his Service as Officer from the United States or State of Virginia. -- That, about three years ago he placed in the hands of Honorable E. K. Kane Senator from Illinois his Two Commissions from Gen. Geo. Clark and Todd, and is informed by Mr. Kane the said Commissions are on file in the War Office at Washington City. That his Commission as Ensign from Gov. Arthur St. Clair was forwarded to H. D. Handy Esquire at Washington City for him to place on file with the others, that he is uninformed if said Handy ever received it. –- In consequence of his Commissions being absent and his old age it is impossible for him to give the months or years the different Services were rendered but thinks it was in the years Seventeen hundred and Eighy one and two. -- That he was about eighteen years of age when he Served under the first Commission, and understood at the time he was doing duty, that he should get Lands and money for his services. That he always done his duty as far as in his power to render aid and Support the orders of his Commanders and the Government by them employed. (signed) Bte janis Sources. As with the transcript of JB's petition to Congress, above, for this one I am indebted to Will Graves and his work at the Southern Campaigns' Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters. His transcription can be found in the first section of the document at Pension application of Jean Baptiste Janis; I made some light edits to his version. To see the images of the actual documents—written in longhand—go to Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application File S. 15,901, for Jean Baptiste Janis, Virginia, and look first for Image 36, and its continuation on Image 35. (Yes, the images seem to have been posted on this webpage in reverse order.) If you download the images, they appear (in the correct order) as 4159865_00970.jpg and 4159865_00971.jpg. Executive Summary. Here, in Jean Baptiste's affidavit, he asserts some facts we already know, but some other previously-unknown factoids as well. Here's a summary of the whole: His effort to secure himself a belated pension had hit an impasse. There was nothing else for him to do, except wait. Click on the link at the bottom of this page for our next exciting episode. This section is for footnotes. For references see Sources & References in Part 2. Butterfield has: The Colonel left the fort in Kaskaskia governed by the militia—about every other one of the able-bodied men enrolling themselves to guard the several villages (p. 307). To me the phrasing here is ambiguous. Does he mean "every other" as in "every other house in this neighborhood is painted white," i.e. 50% of the houses are white? In that case, about half the able-bodied men volunteered to guard the villages. Or does he mean "nearly every other able-bodied man who did not volunteer for the campaign against Vincennes? The latter would mean that 100% of the able-bodied men volunteered in some way, either by going to Vincennes or by staying home to guard the villages. In the introduction of my paper copy of Clark's Campaign in the Illinois, Henry Pirtle notes that in 1771, acting through a London agent named David Blinn, the people of Illinois demanded of the English the right to form their own government. (P. 2 of the introduction: Unfortunately Pirtle does not cite his source, and no amount of googling variations on "david blinn london agent french illinois" seems to turn anything up.) Butterfield twice quotes letters by Colonel Daniel Brodhead (p. 767), whom George Washington appointed commander of the Western Department in 1779: I cannot conceive how he can justify the murder of men who had surrendered prisoners. (Brodhead to Washington, May 29, 1779. —Department of State MSS.) [Clark] took four other officers [besides Hamilton] and about sixty privates, besides some Indians which he killed and threw into the river, which is a part of his conduct I disapprove. (Broadhead

to John Heckewelder, June 3, 1779.) Had he truly disapproved, I would have thought that Broadhead would have taken some sort of disciplinary action against Clark. I wrote the first version of this page in 2015. I write this note in 2021. During these intervening years, a statue of Clark has been one of four sculptures removed from Charlottesville, Virginia amidst considerable controversy. It is interesting that, in my somewhat cursory googling, I have not found the atrocity he committed at Vincennes offered as a justification for the statue's removal. (See, for example, UVA and the History of Race: The George Rogers Clark Statue and Native Americans | UVA Today.) I think there should be a national museum dedicated to banished historical artwork. Perhaps as part of the Smithsonian Institute. Each piece would have a couple of paragraphs of text and audio describing its history as well as the person or historical event it's commemorating—ending with the story behind its banishment. An analysis from an art history perspective would also be interesting.... I would go to such a museum. See the Wikipedia article for an introduction to the complicated story of Illinois's long and frequently half-hearted journey toward full abolition. For a deeper dive check out M. Scott Heerman's The Alchemy of Slavery.

Jean Baptiste's Affidavit

Notes

Militia Volunteers

Henry Pirtle

George Rogers Clark

More Notes on the Massacre of the Indians at Vincennes

Removal of Statue

Slavery in Illinois