Here we continue the story of Jean Baptiste Janis, focusing on his bills before Congress in 1836.

Bills before Congress

In After the Revolution in Part 1, I explained that François Busseron lent nearly $12,000 to George Rogers Clark and was never repaid. That's one perspective. Alberts describes the situation from Clark's point of view—that of a dedicated commander who worked without pay and personally took on debt to purchase supplies for his regiment, assuming that, eventually, he would be paid back by the government which would one day be formed. "Both Virginia and the United States, however, defaulted in payment" (Alberts, p. 62), and his property was confiscated in order to repay his creditors. Finally, in 1838—twenty years after his death—his heirs received a lump sum of $30,000 in return for his service to the country.

As mentioned previously, there appears to have been a movement in the 1830's for the United States to acknowledge its debt to those who had fought for its independence, for, at roughly the same time that Clark's heirs received their compensation, the U.S. Congress debated and passed legislation giving my ancestor, Jean Baptiste Janis, a pension of $10 per month for his stints as a soldier in the Continental Army.

The year 1836 was a busy year for Congress. A list of legislation passed for that year ranges from the important to the mundane, including: appropriations to continue war against the Creek and Seminole American Indians; authorization for a railroad through Massachusetts as well as for post-roads in Arkansas and Missouri; an act extending franking privileges (that is, free mail service) to Dolly Madison; an act to continue diplomatic ties to Spain; and a number of laws concerning patents.

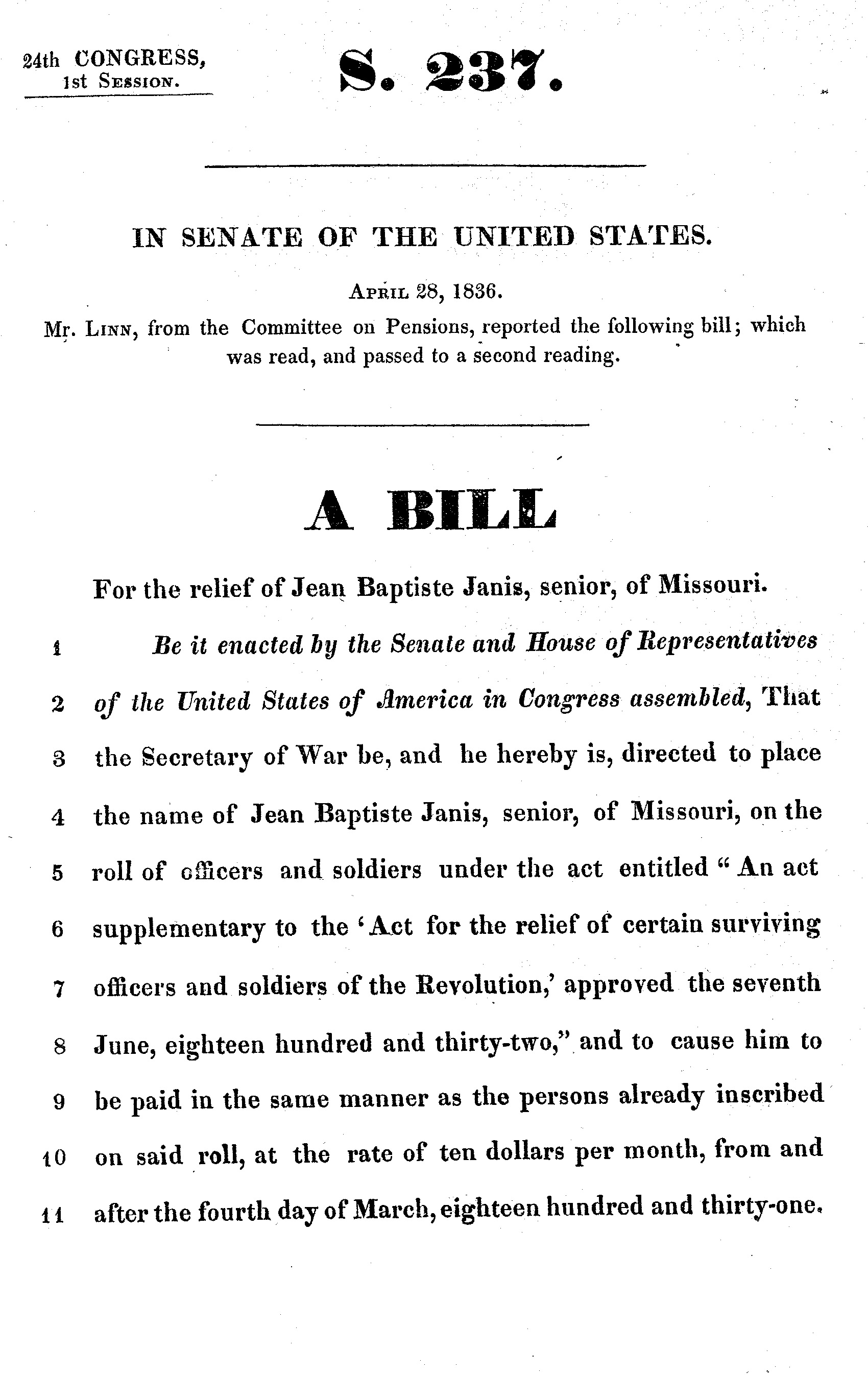

Senate Bill S. 237 of 1836

In the Senate, Jean Baptiste's cause was taken up by his representative, Senator Lewis F. Linn of Missouri. Linn's Wikipedia page is pretty skimpy, but it does mention that as a medical doctor he successfully fought two cholera outbreaks in Ste. Geneviève. Since their lives overlapped in this tiny Missouri town, it is probable that Senator Linn knew Jean Baptiste Janis personally.

Here's the first page of Senate Bill 237, also known as S. 237, 24th Cong., 1st Session, 1836, "For the relief of Jean Baptiste Janis, senior, of Missouri."

The House Bill

On the House side, the petition to Congress was presented by Congressman John Reynolds of Illinois.

John Reynolds

Since Jean Baptiste Janis the Elder was living in Missouri at the time, it makes sense that Senator Linn of Missouri would sponsor the Senate version of the bill. But why would an Illinois representative support Jean Baptiste's cause in the House?

There are two reasons. First, John Reynolds, as he reveals at the very end of his speech before Congress, knew Jean Baptiste personally. Second, over the course of his life Congressman Reynolds had become rather enchanted with the French Creole culture of Upper Louisiana.

In 1800, when he was 12, Reynolds' family moved to Kaskaskia, Illinois from their farm in Tennessee. Later he studied law and in 1812 he returned to Kaskaskia to begin his practice there. He married a Creole woman, and took a strong liking to their culture and lifestyle, more than once referring to them as "a happy people" in his biography. During this time he also learned French, which, according to his Wikipedia page, he considered "as being superior to all others for social intercourse". Ekberg quotes Reynolds speaking of the law-abiding tendencies of these early settlers, declaring that the only crime any French Creole ever committed in Illinois was that of keeping his grocery store open on Sunday.

By the time he died, Reynolds would fill the posts of governor of Illinois, associate justice on the state's Supreme Court, and representative in the Illinois Legislature. In addition, from 1835 to 1837 he joined the U.S. House of Representatives. His tenure there was limited to a single term, as he failed to retain the seat in the election of 1836. During his two-year stint there, however, he took up the cause of a 77-year-old Creole named Jean Baptiste Janis.

That Day in the House

In the spring of 1836, a House version of the Senate bill for Jean Baptiste's pension was drafted. That June, Congressman Reynolds was scheduled to bring it up for discussion before the U.S. House of Representatives.

It was Saturday, June 11, and the House was going through its routine of "the reading of the journal" (which back then meant reading aloud the official record of the previous day's legislative actions) when two newsmen—"one of the regular reporters for one of the city papers, and another who usually reports in the Senate for a distant paper"—got into some kind of squabble. One of the men was sitting at a desk, the other standing before it, and they were engaged in conversation when the reporter standing threw his hat at the man sitting behind the desk, then raised his cane and hit the man behind the desk two or three times. (The Congressional Globe, p. 544 ff)

The disturbance stopped all the regular business in the House, for the record shows the congressmen spent what remained of the morning debating what to do in the matter. Some argued that the House of Representatives had authority to hold in custody only the reporter who did the violence; others, apparently hearing that the man behind the desk had said something insulting to the other, thus prompting the disturbance, argued that the House had authority to hold both in custody. The House then proceeded, and finished, the reading of the journal, and then one member rose and spoke, refocusing the body's attention on the earlier disturbance and what they should do concerning the two men held by the Sergeant-at-Arms. They decided to form a select committee to investigate exactly what had occurred.

Next the House decided that they would have the Sergeant-at-Arms deliver the two reporters to the local police, but they resolved that their doing so should not be interpreted as in any way suggesting that the House had no authority to deal with the disturbance themselves. (The Congressional Globe, p. 545 ff)

Reynolds' Speech Before the House

After all that had happened, Congress was finally able to turn its attention to what had originally been on its agenda for the morning.

PENSION BILLS

The hour from 11 to 12 of this day having been specially set apart for the consideration of "pension bills," and that hour having elapsed, from the length of time occupied in reading and amending the journal,

Mr. WARDWELL moved to set apart the residue of this day for that purpose, which was agreed to.

The House then went into Committee of the Whole (Mr. CRAIG in the chair,) and first took up the following bill:

"A bill extending the provisions of the act entitled 'An act supplementary to the act for the relief of certain surviving officers and soldiers of the Revolution.'"

Mr. C. ALLAN moved to amend the bill by extending its provisions to all those who were engaged in the Indian wars from 1781 to 1795.

This motion was debated then settled, then a few others were moved, debated and settled. Then the House took up and considered 106 pension bills. The source (The Congressional Globe: First Session, Twenty-Fourth Congress, Vol. 3, No. 35) does not provide details on the ensuing debates. However, immediately after this Congressman Reynolds goes on for pages extolling Jean Baptiste and his role in the battle at Vincennes, all in support of our hero's pension.

For the longest time I asked myself why Reynolds was allowed to speak so long for his cause, but none of the sponsors of the previous 106 pension bills was. Then I did some research on a motion from the record, which I quote below: "Mr. WARDWELL moved to strike out the enacting clause." That's when I finally realized that Reynolds wasn't "allowed" to speak on Jean Baptiste's behalf; he had to.

Moving to strike out the enacting cause is a congressional/parliamentary maneuver that forces debate on a bill. (The clearest explanations are on webpages which concern state legislatures rather than the U.S. House. For example, go to https://legisource.net/2020/09/17/second-reading-and-the-committee-of-the-whole-overview-of-rules and search for "strike out the enacting clause.") Mr. Wardwell had no objections to the previous 106 pensions, but the case of Jean Baptiste Janis provoked his ire.

What were Wardwell's objections? While rereading the speech for the umpteenth time in order to to answer this question, I became conscious of the difference between my understanding of the context of the speech and the understanding of Reynolds and all those who were in the House at that moment. In order for us to completely grasp what is going on in this text, we need some essential background information. For example, one piece of this background information is the meaning behind a motion to "stroke out the enacting clause."

Now we have that piece of information, and for this reason we understand better what's going on in the speech. But rereading the text I realized there are two other gaps in our knowledge which I can only partially fill:

1. Everyone in the hall knew what Wardwell's objections were regarding Jean Baptiste's pension. But we can only surmise them from Reynold's remarks.

Reynolds hints that there is more than a single objection, but the only one which I can deduce concerns the fact that the 1832 Pension Act (Wikipedia: "Pension Act") required a minimum of six months' service for even a partial pension, and there was serious doubt that Jean Baptiste Janis served that long during the American Revolution.

2. Everyone there knew what documents Reynolds was referring to, and probably had a full understanding of their provenance and contents.

From this distance we can only hypothesize whether these documents could be some of the documents pertaining to Jean Baptiste's pension which we have explored on these web pages. They are:

- Jean Baptiste's Affidavit, which mentions three terms of service totaling to one year: six months under Clark; three months under Todd; and three months under St. Clair.

- The commissions for his service under Clark and Todd, sent to Senator E.K. Kane, as explained in the affidavit.

- The commission for his service under St. Clair, described in the affidavit as having been sent to H.D. Handy.

- The Petition Jean Baptiste sent to Congress. In Five Signatures, below, I show that the signature on the document cannot be Jean Baptiste's. (Which is not the same as saying that its contents are untrue.)

Forced by Wardwell's maneuver, Congressman Reynolds had to take the floor. Here I provide a transcription of his remarks as recorded in The Congressional Globe: Twenty-Fourth Congress, First Session, Appendix, p. 440 ff). The transcription is literal, which means, among other things, that I have kept the old-style spelling, punctuation and capitalization intact. I break up the text with comments and, for those who are skimming this page rather than carefully poring over its every word, a summary of the most important points.

JEAN BAPTISTE JANIS.

The bill for the relief of Jean Baptiste Janis was then taken up.

Mr. WARDWELL moved to strike out the enacting clause.

Mr. REYNOLDS rose and said:

Mr. Speaker: I do not intend at this late period of the session, and at this time on Saturday evening, to trouble the House with a long speech. I would be pleased if the Clerk will read the commission which Colonel Clark gave to the claimant, appointing him an ensign in a company commanded by Captain Francais Charleville, which commission is now in possession of the House. I would be also well pleased if the Clerk would read the report or statement of the claimant.

[These documents were not read, as their existence and validity were not doubted.]

Reynolds notes Jean Baptiste's commission with Colonel George Rogers Clark, and indicates that a copy is now in possession of the House. Recall that Jean Baptiste's affidavit stated that he had sent his three commissions to a number of government agencies. Fortunately, it appears that one of them resurfaced in time for the debate.

The phrase "the report or statement of the claimant" is the first of two references Reynolds makes regarding a document or documents submitted by Jean Baptiste and held by the Congressional Clerk at the very time that Reynolds was speaking. Could "the report or statement" be Jean Baptiste's Affidavit, or perhaps The Petition? For me it's hard to decide which one would be more likely to be described in this way.

Mr. R. further said that it was a matter of history, recorded and known to the country, that Colonel George Rogers Clark, in the year 1778, marched a regiment to the Illinois country, and on that consideration his corps was called "the Illinois regiment," that on the 4th July, at night, 1778, he entered the town of Kaskaskia with his troops, and captured that place. At the same time there were other settlements and towns in the possession of the enemy near and in the same region of country which at that time was called "the Illinois country."

After taking possession of another village, (Copokia,) which is situated, as Kaskaskia is, near the Mississippi river, Colonel Clark made preparation to capture also from the enemy the military post Vincennes. This expedition was performed in the year 1779. This became necessary, or the conquests already made would not secure the citizens of Kentucky and elsewhere from the inroads made into their country by the Indians, who were inflamed against the Americans by the English. Vincennes was a post which was defended by the British soldiers to the amount Mr. R. could not then recollect; but it was a fort of some strength; and in which, as well as I recollect, Governor Hamilton commanded. In order to be able to succeed in the capture of this post, and thereby to insure peace and quiet to the citizens, Colonel Clark was compelled to enlist into the regiment under his command two companies more. One company was commanded by Captain Charleville, whom I mentioned before, and another commanded by Captain McCarty; one raised in Kaskaskia, and the other in Copokia, and both organized and composed a part of "the Illinois regiment," under the command of Colonel Clark.

Reynolds describes Clark's capture of Kaskaskia and "Copokia," which surely means Cahokia. The error must be one of transcription, as Reynolds' familiarity with that part of Illinois cannot be doubted. Still, there are some phrases in this section of the speech which suggest that he was working from memory rather than a recent, careful rehearsal:

- "Vincennes was a post which was defended by the British soldiers to the amount Mr. R. could not then recollect"

- "and in which, as well as I recollect, Governor Hamilton commanded"

Maybe Reynolds hadn't anticipated the motion to strike out the enacting clause and was speaking off the cuff. Or perhaps he had anticipated the motion, but assumed that he remembered the story well enough to recount it without preparation

The claimant of this pension, Jean B. Janis, was, as I before stated, appointed an ensign in the company commanded by Captain Charleville.

These are all historic facts, which are on this occasion not questioned or doubted, and in fact are admitted.

It is also a fact that Colonel Clark commenced this campaign from Kaskaskia to Vincennes, in the winter or spring of the year 1779, at a time that it was extremely difficult and almost impossible, from the inclemency of the weather and the high stage of the water between those two points, to march his army from one post to the other. The distance is one hundred and sixty or seventy miles. The country at the time the march was performed was greatly inundated with water, and the rivers (the Wabash and others) were so high that the waters were from bluff to bluff in them, and in some instances two or three miles wide. The snow and the ice had not entirely left the ground; and add to this, that there were no baggage wagons, and, in fact, not much food, to attend the army. Yet, with all these privations, hardships, and difficulties, these brave soldiers, under the command not only of a brave but also a talented man, accomplished their march to Vincennes, and took that post from the enemy without the loss of a man.

In this campaign the claimant, Mr. Janis, performed service as an ensign in the company commanded by Captain Charleville, He went, and, like others, acted well his part in that campaign. There is not on record the history of a campaign that exhibited more talents in the plan, and required more interpidity and courage in the execution, than the campaign planned and executed by Colonel Clark in the capture of the British posts on the Mississippi and in the Illinois country.

Reynolds describes for his colleagues the story of the difficult march toward Vincennes through flooded plains and with little food, and furthermore, despite these hardships, the successful siege of the fort without a single casualty. He says the siege "required more interpidity and courage" than any other (the word interpidity appearing to be an obsolete form of intrepidity).

At that day there were very few people settled west of the mountains, and these few were infested and eternally annoyed by the Indians, excited to murder and bloodshed by the British enemy. It became necessary, therefore, in order to secure the peace and quiet of these settlements, to capture these British posts, by which the Indians were supplied with the munitions of war, and to remove back the Indians and the means of their support to such distance as they would not be able to disturb the white people. This was accomplished. More was accomplished, also; the country was taken and retained from the enemy, which now composes the best and the fairest portion of the Union.

In the treaty of 1783 with Great Britain, the capture and occupation of this country by the American arms is adverted to, and, no doubt, was taken into consideration at the time of making the treaty. This is the country that was captured from the enemy by the energy and bravery of Janis, and others, that now pours into the Treasury of the United States so much money from the sales of public lands. There are millions received from the sales of the very same lands which the "Illinois regiment," in which Janis acted as an officer, took from the enemy at a time that "tried men's souls." Yet the honorable chairman says, if a pension be given to Mr. Janis, it will form an exception, and violate the general rule and law on this subject. Be it so. I should consider it an honor to violate a rule that would deprive a man of a pension, made under circumstances such as these. The gentleman [Mr. WARDWELL] seems to represent this case as a person with gold weights, weighing out money by the cent, to a revolutionary soldier who performed so brave and noble a part in that struggle as did Mr. Janis.

a time that tried men's souls: A reference to the first sentence of Thomas Paine's The American Crisis. Also an indirect reference to George Washington, who famously had his officers read the essay to his troops the day before the Battle of Trenton. The reference is very apt, especially when the full context of the reference is considered regarding Jean Baptiste's petition:

These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it NOW, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.

Today we are familiar with only the first sentence, but surely back then many people, certainly most of the population able to read, were familiar with the "summer soldier and sunshine patriot" line.

Reynolds argues that Clark's capture of the British posts in the Illinois Country served two purposes: it kept the Indians at bay and played a central role in the peace treaty finally made with the British to end the war, ceding this valuable land to the Americans. Some historians have made the same point, arguing that, had Clark not taken and held the British posts, England might well have retained the territory during the negotiations (though the contention is much debated).

Congressman Reynolds addresses arguments against the case of Jean Baptiste Janis, posed by Congressman Wardwell. Apparently Wardwell had argued that to give Jean Baptiste a pension would prove an exception to the requirements previously laid down by laws on pensions, to which Reynolds declares it would be "an honor" to violate such a rule in this case. Later Reynolds will discuss the details of the rule that disqualified Jean Baptiste from a pension.

Finally, notice the language Reynolds uses when referring to the Indians—infested, murder and bloodshed, and disturb the white people. No doubt this is how the Americans tended to think of the Native Americans—how else could they justify in their minds their own slaughter of an entire people? In a previous section of this speech, Reynold says, "This became necessary, or the conquests already made would not secure the citizens of Kentucky and elsewhere from the inroads made into their country by the Indians." Note that the complete lack of awareness of any irony in claiming that the Indians had been making "inroads" into the white men's country. (And this is a "good guy"!)

But let us stop there and continue with the speech.

I will call to the recollection of the gentleman the privations and hardships on the march to capture Vincennes. Did Janis, when he was wading in the snow, ice, and water, to his neck, think of weighing out his energies and bravery with gold weights? Did he at that time think he was violating any rule, (and "his case would form an exception,") when he was fighting before the post of Vincennes? Nice conscientious scruples, and gold weights, were at that time not considered by Janis, and now should not be by us. We are now reaping the fruits of his and their labor; and I am, as one individual, in legislation or otherwise, proud to acknowledge it. We are now at our ease, happy in every respect, reclining in the shade of "the vine and fig tree," which was spoken into existence by the energies and talents of the revolutionary soldier. We are their happy children, and I hope we will have the gratitude to sustain, in reclining life, the few of our revolutionary fathers that remain among us. They cannot live among us only for a few years. The gentleman for whose benefit this bill is brought before Congress is far advanced in years, and cannot, by the course of nature, live long. I am informed he is about eighty years old. This bill, which only provides ten dollars per month during his natural life, will not beggar the Treasury, and will be an honorable acknowledgement of his revolutionary services. It will be a proud boon to his numerous and respectable descendants.

Reynolds again mentions the hardships of the march to Vincennes, and declares it unseemly that now, living in comfort with the war behind them, the members of Congress are willing to enjoy the benefits of Jean Baptiste's efforts without being willing to acknowledge his services.

to recline in the shade of the vine and the fig tree: that is, to live in peace and prosperity. This is a Biblical reference. (See Of Wars, Vines, and Fig Trees .) It could also perhaps be another indirect allusion to George Washington, who apparently was fond of the Biblical reference himself. (See Vine and Fig Tree.)

They cannot live among us only for a few years: This phrasing seems very awkward, even for a 19th Century American politician. Surely Reynolds means to say, "They can live among us only for a few years more."

he is about eighty years old: In fact, those of you who have been paying attention know that Jean Baptiste was born in 1759, which made him 77 in 1836.

The gentleman [Mr. W] says the case of Janis, if it becomes a law, will violate the existing law on the subject of revolutionary pensions. This is true, I presume. If the claim of Janis was embraced in the principles of the law now in existence, there would be no necessity of another act for his benefit. This claim would be allowed and paid under the provisions of the present law. The reason the old law does not embrace his case, is the foundation of the present application to Congress. The gentleman further says that, from all the information he can obtain, Mr. Janis served only thirty-six days; and as the law requires a service in all of six months in the Revolution to entitle a soldier to a pension, that, on that consideration, he is not entitled to a pension. Even to go with the gentleman into this rigid and strict rule, requiring proof of six months' service, it can be fairly presumed that, in the absence of evidence, Mr. Janis was six months in service. The gentleman would not require six months of continued fighting in a serugs battle, nor would he require six months' wading in snow, ice, and water, to entitle the soldier to a pension. The service which was so honorably performed by Colonel Clark in capturing these posts would require six months or more for its execution; and the fair presumption is, that Mr. Janis was employed in the service under Colonel Clark for six months or more during his conquest of the Illinois country.

The evidence spoken of by the gentleman [Mr. W.] cannot be correct. It would require more than thirty-six days for the army to march, at that season of the year, from Kaskaskia to Vincennes, and return. There were no bridges or ferries at the time, and the route was almost impassable from the snow, ice, and high waters in the rivers and other streams. In this calculation there would be no time left for preparation and organization for the campaign at Kaskaskia before they started, and no time left for the capture of the post, (Vincennes,) and for its occupation by the American forces. Every reasonable man will know it will require more than thirty-six days for the performance of this expedition. I do not want for Janis any thing that is not right and proper—he, himself, would not receive from Government or any individual any thing that was not strictly honorable and correct. He is a gentleman whose character for honesty and integrity stands above suspicion.

a serugs battle: a battle in which all on both sides are killed (definition given in the record itself).

In this passage Reynolds directly addresses the argument against giving Jean Baptiste a pension: that the law required six months of service, whereas the Battle of Vincennes took at most 36 days. The congressman from Illinois argues that, while the march and the siege themselves might have taken just 36 days, the preparation for the battle, and the occupation of the fort after the battle, would easily have required six months or more. In essence he is distinguishing the amount of time a soldier is enlisted from the amount of time the soldier spends on a mission (as in marching toward Vincennes) or in combat (as in attacking the fort). His point is that six months' enlistment is what the law requires, not six months in actual battle or even on march.

I read a printed statement of his services, which lies on the Clerk's table; and I know not now if it were his own statements or a report of a committee—I would believe one as much as the other; I will vouch for his statements to be correct. I have known him and his character from my youth, and I know it to be good; and on this occasion I consider it my duty to state it, although he is not my constituent, but a resident of the State of Missouri.

Next the congressman refers to a "printed statement of his [that is, Jean Baptiste's] services." This is the second reference to some document whose origin and contents we are not privy to. Is this the same document as the first, described as a "report or statement", or is it a completely different document? And, just as with the previous reference, we have to wonder whether this might be Jean Baptiste's Affidavit, or perhaps The Petition.

I am fairly convinced that, here, Reynolds could not be referring to the affidavit. At this stage of the speech he means to establish the fact that Jean Baptiste served at least six months for the Revolution. In the affidavit Jean Baptiste asserted that his service under three different commanders totaled a full year. If Reynolds was referring to the affidavit here, surely he would use those assertions to make his point. But he doesn't. Instead his argument is simply to say that compensating Janis for his service, however long it may have lasted, is more important than adhering to the strict wording of the Pension Act.

Moreover, he is coy about who actually authored the statement, Jean Baptiste Janis or "a committee." This question of the document's provenance suggests that it could be the Petition, which was probably written in 1836, when Jean Baptiste was possibly quite infirm, and, in any case, certainly wasn't signed by him (as we explore in Five Signatures, below).

It may be, Mr. Speaker, from the fact that I have been raised in the country where this service was performed, and on that consideration have heard so much about it, of its perils and hardships, that I have become so well convinced of the justice of the claim of Mr. Janis. It seems to me to be a claim of such propriety and justice that the House cannot hesitate to allow it. The gentleman need not fear that this case will open a door for similar cases. There are none in our country, as I know, similar to that of Mr. Janis; but if there were, it would be just and proper to allow them. I hope the House fully comprehend the merits and justice of this case, and knowing it, will allow it.

After some remarks from Messrs. WARDWELL, STORER, and ASHLEY, the bill was ordered to a third reading.

a the bill was ordered to a third reading: In the House, legislation must be "read" three times before it can be passed.

Reynolds closes his arguments by vouching for Jean Baptiste's character. Here we learn that he and Jean Baptiste have known each other since Reynolds was a child. Reynolds goes on to explain that, having grown up in Illinois, he has heard many times the story of the Battle of Vincennes. He admits that this may be why he is "so well convinced of the justice of the claim of Mr. Janis."

Addressing the concern of Wardwell, and others no doubt, that Jean Baptiste's claim constitutes and "exception" to the established practice for pensions, Reynolds says, "The gentleman need not fear that this case will open a door for similar cases. There are none in our country, as I know, similar to that of Mr. Janis." But how can this be true? As we learned in Part 1's The Creole Volunteers, there were 79 other Creole volunteers who signed up for Clark's campaign. Wouldn't their claims be more or less the same as Jean Baptiste Janis's?

Another yet doubt must be raised, one over Reynolds' claim that he has known Jean Baptiste Janis "from his youth." Here's the chronology, to the best of my knowledge:

- Before 1800: Jean Baptiste receives 8,000 acres from the Spanish government after he moves to the Ste. Geneviève, Missouri side of the Mississippi. (The Petition)

- 1800: France regains Upper Louisiana from Spain.

- 1800: John Reynolds' family moves from Tennessee to Kaskaskia when he was 12. (Wikipedia)

- 1803: The Louisiana Purchase transfers Upper Louisiana from France to the United States.

- After 1803: Jean Baptiste loses his 8,000 acres on the transfer of the Louisiana Territory to the Americans (the Petition).

We don't know the exact date of two of those events, but we do know the timeline of them all. On the west side of the Mississippi River, Jean Baptiste received his 8,000 acres from Spain before 1800, because Spain lost sovereignty to the territory in 1800. Yet John Reynolds didn't live in Upper Illinois until 1800, and when he did he was on the other side of the Mississippi.

I suppose that, homeless, Jean Baptiste could have moved himself and perhaps his family back across to the Kaskaskia side of the river after 1803, where Reynolds could have come to know him. But the move seems unlikely. In The Janis Family, where I explore what happened to J.B.'s family after the American Revolution ended, I quote Alvord as saying that Nicolas (the father) was the last of the family to leave for Ste. Genevieve, and that was in 1790 or '91. Why would a homeless Jean Baptiste go back to the Illinois side when all his family had by then moved to the Missouri side?

I don't mean to argue that John Reynolds was intentionally lying when he made this claim before Congress. Maybe as a teenager he was inspired by the story of the Campaign against Vincennes, and hearing it told by people who had known Jean Baptiste at the time made him feel as though he too knew our hero. Maybe when he was young, once or twice, Jean Baptiste was pointed out to him in the street, either in Kaskaskia or across the river in Ste. Genevieve, and this sighting attached itself to all the stories he had heard. And maybe when he married his Creole bride and fell in love with her ethnic background and took the time to learn French, maybe he felt as though he had by marriage become a relative of all the Kaskaskia Creoles, which would naturally have included its most prominent family, the Janis.

Success?

The most obvious question is—well, did Jean Baptiste get the pension or not?

Lankford says no:

Sadly, even Jean Baptiste Janis's attempt to gain a pension for his heroism at the capture of Vincennes turned out badly. He apparently applied in the twilight of his life, and he must have done it incorrectly—he probably just wrote a letter. In 1833 he received from the government agent a copy of the printed Revolutionary War pension rules with a note saying that if Janis wished to obtain a pension, he would have to submit a request by the rules. Three years later Janis was dead at 87, and the note was left among his effects. Sainte Geneviève Archives C 3636, Folder 401, WHM. See also the Lyman Draper Collection, the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison:18J92-93. (Lankford, p. 180)

First of all, either Lankford has the wrong date for Jean Baptiste's birth, or he does his math badly: Jean Baptiste was 77 when he died, not 87. There is ample documentation that his birth year was 1759, much of it cited on these pages, and this is confirmed by the affidavit wherein he states he was 74 in 1833.

Concerning the question of whether Jean Baptiste got his pension, the Lankford article was published in 1995, and no doubt it was written a year or two before then. It turns out that Jean Baptiste did in fact win his pension. Which gives me the opportunity to rewrite history, at least a little bit.

Genealogically speaking, a major seismic event since Lankford's 1995 article has been the creation and growth of the Internet. Many private and government documents, previously buried in obscurity, have been given a new life as archives around the world make their holdings publicly available on the World Wide Web. Readers of this website have benefited from this renaissance: to cite but one example, this page mentions Jean Baptiste Janis's affidavit to Congress, which, until very recently, was all but unknown to anyone other than a few very specialized scholars.

My first attempt to research this question occurred during a time that the Library of Congress was "digitizing" (i.e. putting on the Internet) the very records I was looking for. I detailed the complicated process on the original version of this very web page, but have since moved those notes to Original Jean Baptiste Janis Research.

This second time around has turned out to be nearly as difficult, though, I hope in the long run, it will be more permanent in that the links now send the reader to websites much better anchored in the internet, being on long-lasting websites rather than fly-by-night URLs.

The Law

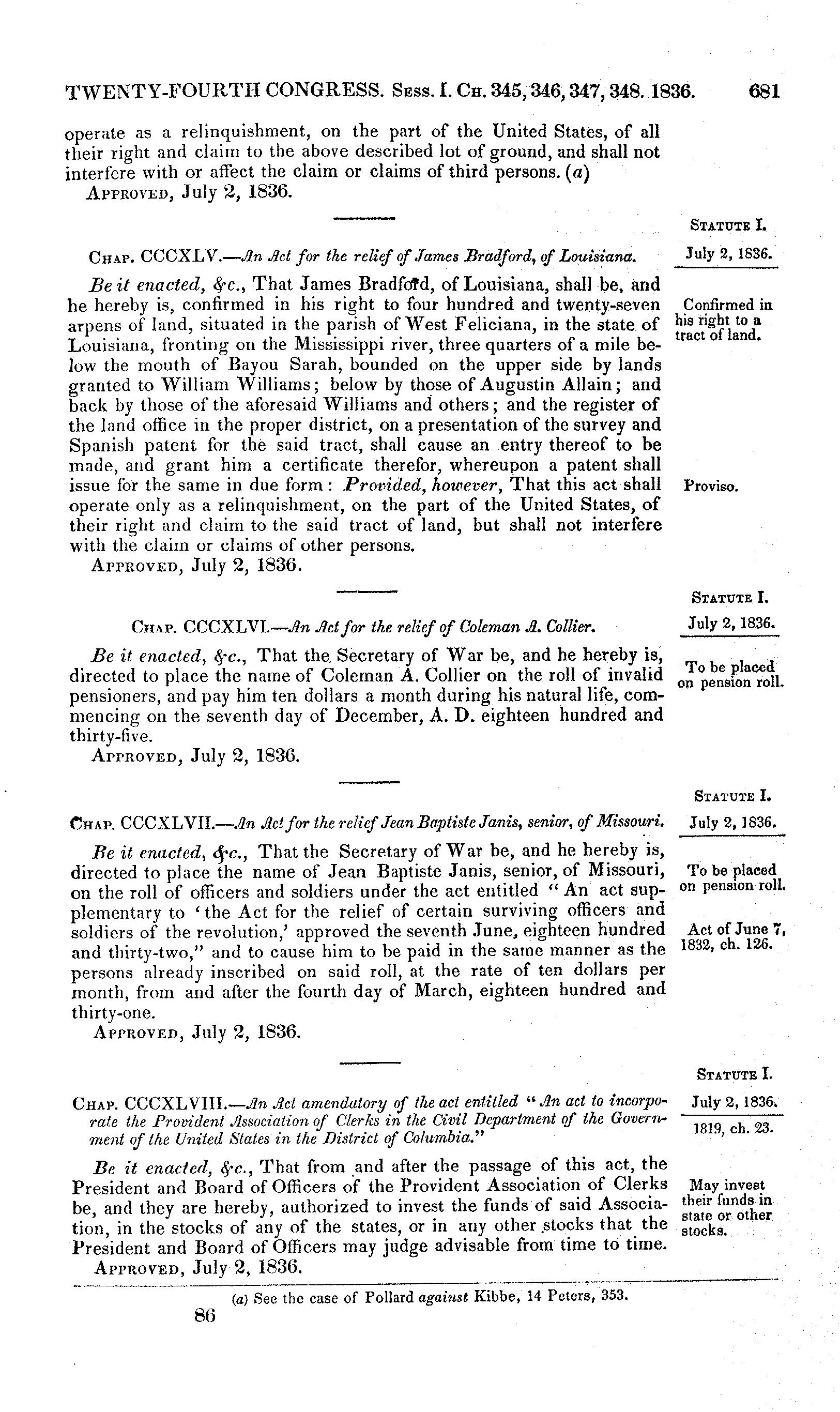

We've seen both the Senate bill and the House debate. As you'll recall, before a bill becomes law the two versions must be reconciled and then signed by the president. That must have been what happened, because here's the law itself. (For J.B. Janis's "chapter," see the fourth section, where the first section is the one being continued from the previous page. View the page online at Private Act for Jean Baptiste Janis, 24th Congress.)

For the (searchable) record, here's what the law concerning Jean Baptiste reads:

CHAP. CCCLXVII.—An Act for the relief of Jean Baptiste Janis, senior, of Missouri.

Be it enacted, &c., That the Secretary of War be, and he hereby is, directed to place the name of Jean Baptiste Janis, senior, of Missouri, on the roll of officers and soldiers under the act entitled "An act supplementary to 'the Act for the relief of certain surviving officers and soldiers of the revolution,' approved the seventh June, eighteen hundred and thirty-two," and to cause him to be paid in the same manner as the persons already inscribed on said roll, at the rate of ten dollars per month, from and after the fourth day of March, eighteen hundred and thirty-one.

APPROVED, July 2, 1836

So now we have answered the most obvious question—did Jean Baptiste get the pension or not? The next most obvious question is—given that he died the same year the law giving him a pension was passed, did he even get the news when Andrew Jackson signed it into law? ... Not surprisingly, however, there's no record of whether or not he got this news, or any news at all about the bill.

Therefore let's instead ask whether or not it was possible that he got the news of the statute's being signed into law.... Unfortunately, I haven't been able to find the exact date on which Andrew Jackson signed the bill.

Which requires us to rephrase the question again. Immediately above we see that the law was "approved" on July 2nd. Was he still alive then? ... Yes, he was. Jean Baptiste died on October 22nd (https://www.nps.gov/people/jean-baptiste-janis.htm). So it is certainly possible, indeed likely, that he got the news of the bill's passage out of Congress. And that may have been all the assurance he needed, for it turns out that Andrew Jackson vetoed only 12 bills in his two terms as President, and none of them had anything to do with pensions for former soldiers. (https://www.senate.gov/legislative/vetoes/presidents/JacksonA.pdf)

How about another question? Did he or his heirs ever see a penny of the pension? Good question! In the File View subsection on my Janis Notes page I cover a letter from Senator Linn to the Commission of Pensions, James Edwards, in which Linn states:

By a special Act of Congress the name of John Baptist Jannes was placed on the Pension List for revolutionary, in 1835 I believe, he received a portion of the pension and died some time in October of the same year. I wish you to inform me whether there is not a balance due his heirs.

I think we can therefore conclude that J.B. or his heirs definitely received some money, but there is reason to wonder whether the heirs received the entire amount that was due. (By the way, one question I have not been able to answer concerns how long the monthly payments were supposed to continue after Jean Baptiste's death.)

Five Signatures

In the previous section we asked whether it was likely that Jean Baptiste Janis ever received the good news that his request for a pension was passed by Congress and signed into law. And we decided that it was likely. In this section I provide some findings that make you wonder whether he was capable of understanding the good news when it came.

Alas, however, the information has to, in the end, be chalked up to just another historical/genealogical mystery which will probably never be resolved.

I have five different signatures belonging to Jean Baptiste Janis, all of which look very different—even those made within a week of each other!

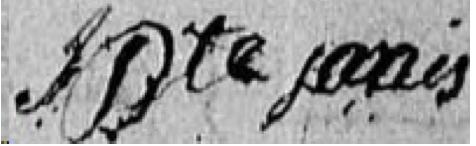

Chronologically, the first comes from his 1781 marriage contract, documented in these pages under Marriage of Jean Baptiste Janis. He was about 24 at the time.

It is obvious that Jean Baptiste spent some time honing this signature before releasing it into the world: That flourished "B" is very self-conscious. Interestingly, like his father, Nicolas, he begins his surname with a lowercase letter "j" (Baptism of Antoine, Note 4), yet his "j" is distinct from his father's.

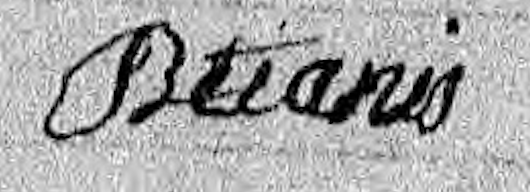

The next signature we have is from 50 years later, on a document giving power of attorney to his relative, William Gibson. (To verify this and the remaining signatures yourself, see the "References" section below.)

When I saw this, my first thought was that it must be a forgery. Then, after considering that the document in question was a power of attorney, I thought that Jean Baptiste might have recently suffered a stroke severely limiting the use of his dominant hand. Or a stroke forcing him to use the other hand entirely.

Those explanations were both quashed when I had a look at the next signature, our third, coming from the affidavit he signed while trying to get his pension. Recall that I provided the transcription of Jean Baptiste's Affidavit in Part 1. The affidavit itself is undated, but the subsequent legal documents asserting the affidavit's validity have dates. The handwriting on the first is a little hard to read, but appears to be dated April the 14th or 15th, 1833. The next two are dated the 16th of that same year.

It immediately seems apparent that this signature and the first have more in common than either does to the second, so let's focus on those two. True, they differ significantly. But that shouldn't surprise us, when we consider that over fifty years have passed between them, a time during which Jean Baptiste's own, French Creole culture—with one set of signature aesthetics and common practices—has been entirely eclipsed by a very different culture altogether.

- The two "B"s are in completely different styles.

- Baptiste is abbreviated in two different ways.

- Still, the surname in both seems to me probably from the same person, though I admit that the "a" in the first is a little more flourished than the second. In fact, to the extant that "flourished" characterizes the first signature, the second seems ... let's say, "labored".

I may be letting my imagination get away from me, but it looks like the intervening half-century has treated Jean Baptiste Janis rather unkindly.

The fourth signature comes from the pension application of François Charleville, where we have an affidavit signed by J.B. on behalf of the heirs of François Charleville, his captain when he served under Clark. They, too, were seeking a Revolutionary War pension, though Charleville himself had died in the 1790s.

This signature resembles the second in the same way that the first approaches the third.

By the way, in that same application it says Charleville's heirs also gave power of attorney for someone to handle their pension application. So perhaps I am mistaken when I imagine that assigning power of attorney to someone for this task could be an indication of stroke or some other mental or physical handicap.

A Second Look at the First Four

Thus far we've looked at the signatures with one separated from the next by text. To make it easier to compare each one to all the others, I'll make each image smaller and display them one right after the other. Also, instead of presenting them chronologically, I'll order them from most fluid to most strained, which turns out to be: Signature 1, Signature 3, Signature 4, Signature 2.

I was jarred the first time I looked at this presentation of the signatures. You can clearly see—or imagine you're seeing—an indisputable evolution from one signature to the next. In other words, there's enough similarity between any signature and the one which follows that you can easily believe that they all came from the same hand. Especially if you allow for the possibility of some severe injury happening towards the end.

There are two problems, though. First, the timeline—the chronological ordering of the signatures—doesn't agree. How could the second signature chronologically be the one most suggestive of infirmity? It makes me wonder if my dating is, somehow, incorrect.

The second problem is that the next signature I'll share with you, the fifth chronologically, doesn't fit in at all.

The Fifth

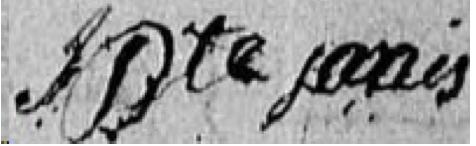

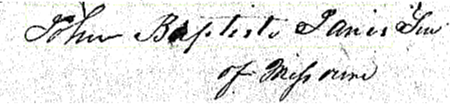

Now have a look at the fifth and final signature, below, which comes at the end of The Petition that Jean Baptiste sent to Congress in, I believe, 1836— that being the year in which the House and Senate finally took up his petition.

For myself, I struggle to find any points of similarity between this and the previous four. I believe it must come from a different hand altogether.

- The capital "B" which Jean Baptiste seems to have adopted by the 1830s is gone, replaced by one of a completely different style.

- The lowercase "j" with which he begins his surname Janis, a trademark except for the half-crippled signature on the power of attorney document (where it's a lowercase "i"), is now capitalized.

- Compare the tilt of the lines crossing the "t"s. The line on the last signature is almost perfectly horizontal.

- There are other differences, at first glance minor, perhaps, but which I suspect are identifying characteristics of a person's handwriting. The dot above the "i" in the surname, for example: the writer of the fifth signature has put it directly over the main part of the letter, whereas the real J.B. dots his "i" a little to the right.

What stands out more than anything else, however, is how anglicized the signature is. The French Creoles rarely spelled out the entire name "Jean Baptiste." Usually they would shorten it, to "J. Bte" or even just "Bt." as the first four signatures attest. This was because "Jean Baptiste" was so ubiquitous that only a couple of letters were needed to indicate the full name. But the Americans back in Washington wouldn't know that. And maybe whoever signed the petition for J.B. didn't know it either. And while we're at it, they might have said—Jean Bte. and the person or persons helping him—why not translate Jean to John, so that he would appear as American as he could possibly be?

So somebody else had to sign the petition for him. The reason might have been geographical: the person who penned the draft was in Washington D.C. (maybe Senator Linn, or Congressman Reynolds), and Jean Baptiste Janis was nine hundred miles away in Missouri. Or maybe the reason was physiological: by this time, three years after the stroke I imagine he suffered, he was unable to pick up a pen and use it.

Two other observations:

- I have gone through all the handwritten documents in Jean Baptiste's file at the Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty webpage, and none of them has handwriting which resembles this. Or so it seems to me.

- The Petition begins, "Oppressed with age and infirmity." We have to wonder, what infirmity? The one that left him unable to sign his name? And if it was a stroke, how bad was it? Did it affect his ability to speak as well? To carry on a conversation? To understand the good news, when it eventually arrived, that he had won himself and his heirs the pension?

"Five Signature" References

Signature 1: Marriage of Jean Baptiste Janis. Look for the second page of the marriage contract.

Signature 2: See Image 32 and 31 at Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application File S. 15,901, for Jean Baptiste Janis, Virginia. (The document begins at Image 32 and ends at 31; that is, they are numbered in reverse. If you have downloaded the files, they are files 4159865_00974 and 4159865_00975.)

Signature 3: For the affidavit see Images 36-35 at the Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty link given above. (If you have downloaded the files, it starts on 4159865_00970 and ends on 4159865_00971.) The first legal document asserting the affidavit's validity is on the same page as the end of the affidavit, Image 35/Downloaded file 4159865_00971; the next two are on Image 34/Downloaded file 4159865_00972.

Signature 4: See Pension Application of François Charleville. The file also provides the approximate date of Charleville's death and the detail regarding his heirs' assigning power of attorney.

Signature 5: Again from the Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty webpage, where the four-image document starts at Image 28 and ends at Image 25 (4159865_00978 through 4159865_00981 if you've downloaded the files).

Sources & References

Generally speaking, when I'm citing an online source on this website I provide the link there in the text. But for the Internet resources below, I want to add some additional information. That's what you'll find here.

Archival Records

When writing the original version of these pages on Jean Baptiste, I didn't have much archival material. But, as I've noted elsewhere on this page, much more has become available.

Southern Campaigns' Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters

One of my original sources, this is a website whose aim is to increase American awareness of the contribution of the South in the War for Independence. On this website, scholars Will Graves and C. Leon Harris have posted their transcriptions of some of the original documents archived in various libraries. It is only by chance that Jean Baptiste's records appear here: George Rogers Clark served in the Virginia militia, which meant that Jean Baptiste was technically part of the South's war effort, though it seems that all of his service lay north of the Ohio River. There are two mentions of Jean Baptiste in these records.

The first, Pension application of Jean Baptiste Janis, discovered in June 2017 and still alive in 2025, provides the transcription of a couple of pages of a 39-page ("f39VA") file on Jean Baptiste. The document has four sections.

- The first is the text of the affidavit taken under oath concerning JB's service, which I have mentioned a couple of times on this page, and which is summarized here.

- The second section consists, in its entirety, of this single note: "[p 8: In a power of attorney executed April 10, 1833 by the veteran he refers to his attorney as 'his relative William Gibson.']"

- The third section of the document is the most interesting, being his petition to Congress, which is quoted whole on these pages in The Petition.

- Finally, at the very end, is another one-sentence note, reading, "[Veteran was pensioned at the rate of $120 per annum commencing March 4th, 1831, for service as an Ensign in the Virginia service.]".

The second mention of Jean Baptiste in the War Pension Statements, Pension Application of François Charleville appears to be another affidavit taken under oath to assist in the pension application of his commanding officer during the Battle of Vincennes. I have not attempted to find out whether Monsieur Capitaine was also compensated by the American government.

While doing my research for this brief history on Jean Baptiste Janis, I had an Email Exchange with Will Graves at the Southern Campaigns website.

Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application File S. 15,901, for Jean Baptiste Janis, Virginia

In my second round of researching and rewriting these pages on Jean Baptiste Janis (a process I began in order to fix the many broken internet links), I came across this, the original 39-page file, which Will Graves had partially transcribed. (See source above.) In these pages I have provided transcriptions of the two most useful items--JB's Affidavit and his Petition to Congress. For both of these I began with Will Graves' transcriptions (see Southern Campaigns, above), compared those to the .jpg images available at this website here, and made modifications based on my reading of the original.

Two points:

- As I've mentioned elsewhere, the images which this source makes available are in reverse-order. In other words, for a multi-page document, the last page comes before the first. But if you download the images (and/or the OCR text files), you can sort them by filename to put them in the correct order.

- I have gone through all the .jpg images and, for any I found mildly interesting, fixed the OCR text. These transliterations form just a part of the detail provided in my notes at Jean Baptiste's Pension Application.

Histories

Here are the sources which I found as I learned about the Battle of Vincennes.

- Lankford, George E. (1995). Almost 'Illinark': The French Presence in Northeast Arkansas. In Jeannie M. Whayne, Cultural Encounters: Indians and Europeans in Arkansas (pp. 88-111). Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. Some excerpts from the article can be found in Google Books. You'll also find a PDF copy in Hard-to-Find Sources.

- Consul Wilshire Butterfield. (1904). History of Lieutenant-Colonel George Roger Clark's Conquest of the Illinois and of the Wabash Towns from the British in 1778 and 1779. (Available from the Library of Congress at https://www.loc.gov/item/04007344/.) Butterfield's approach to history is meticulous, and for this reason the work is admirable, though I do acknowledge that his use of language is dated, frequently referring, for example, to Native Americans as "savages" (and even at one point referring to a group of them as "Hamilton's dusky allies," p. 324). I suppose that in this way the practice of history sometimes borders on anthropology.

- American Battlefield Trust: "Vincennes: Siege of Fort Vincennes / Siege of Fort Sackville,", accessed August 2025. I find this description of the battle to be the most digestible of the sources listed here: it's short yet clearly written, and has a very useful map.

- Bowman's Journal. As I finished reading "Captain Bowman's journal," I began to doubt that Captain Bowman could truly have written it. But none of my sources at the time, including Wikipedia (see below), mentions that Bowman might not have actually authored it. So I was glad to see by doubts corroborated by Butterfield (Note CXXII, p. 765ff). It is probably a genuine first-hand account, but was probably not written by Captain Bowman.

- Wikipedia: "Siege of Fort Vincennes," Wikipedia, accessed June 2017. This article is typical Wikipedia—serviceable, with some nice illustrations, but not always a pleasure to read.

- Lampman, Charles R. "Battle of Vincennes: Victory for G. W. Clark," Revolutionary War Archives, accessed June 2017. This page is fairly informative, but it does tend toward the hyperbolic and needs proofreading. As of 2025, the website is down, but the page is available on the WayBack Machine. (For an example of how to use the Wayback Machine, see The Original and a Rival English Translation)

- Alberts, Robert C. (1975). George Rogers Clark and the Winning of the Old Northwest. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Available online in June 2017, this document is very thorough and has some excellent maps. When you click on the link you will start a download of the .pdf file, which is about 65 pages long.

- "Fort Sackville," George Rogers Clark National Historic Park, National Park Service, accessed June 2017. The site of the Battle of Vincennes, Fort Sackville, is now part of the George Rogers Clark National Historic Park. This page provides a brief description of the fort and its history.

- Nestor, William. (2012). George Rogers Clark: "I Glory in War". University of Oklahoma Press.

These other sources contain interesting historical or genealogical information.

- Ekberg, Carl J., "Colonial Illinois: The Lost Colony", Illinois History Teacher, Illinois Periodicals Online, accessed June 2017. This article—possibly taken from Ekberg's French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times—discusses the cultural differences between the French Creoles in the Illinois Country and the American pioneers who came after them.

- Belting, Natalia Maree. (1945). Kaskaskia Under the French Regime, University of Illinois Press. This short monograph is full of cultural and genealogical detail, and is an excellent starting point for learning more about French Creole society during the 1700s. At one point there was a .pdf version online, but I've lost the link. Fortunately, however, you'll find a copy in Hard-to-Find Sources.

- Alvord, Clarence Walworth, ed. (1909). Kaskaskia Records (1778-1790) is a collection of Kaskaskia primary sources which in 1909 Alvord felt were valuable and yet too difficult for researchers to gain access to. In our age of the Internet I doubt the book would have been published; rather, the documents would have been scanned and posted online. I have not read it end to end, but do have some notes on what I've read so far at Notes on Alvord's Kaskaskia Records (1778-1790). One nice thing about the book is that it provides English translations of all the documents written in French. My French reading skills are pretty good: even so, I am happy to admit that I find these translations to be a great convenience.

-

Reynolds, John. (1879). Reynolds' History of Illinois: My Own Times: Embracing Also the History of My Life. In the early pages of his biography Reynolds has much to say about the Creoles living in Illinois in the days of Jean Baptiste Janis. At least two searchable versions of the book can be found online: at Living History of Illinois and the Google Books version.

-

Who Do You Think You Are?, Season 6, Episode 8. It appears my family is related to pop singer Melissa Etheridge via Jean Baptiste Janis. There's a TV show called Who Do You Think you Are?, in which, apparently, celebrities react with astonishment or anguish over the results of the hard genealogical research which others have done for them. (Thus taking all the adventure out of their genealogy.) YouTube has a number of versions of the episode, for those who are interested. I appreciate the careful notes of genealogist Janis Sellers on the episode—though I feel obliged to mention she's a bit of a show-off when it comes to her French. Sellers' page has a lot of genealogical information worth exploring.